At the beginning of the pandemic, calls to action abounded: “support your local business!” “get takeout delivered, support restaurants!” But it seemed like not enough people listened. 17 percent of US restaurants permanently shut down in 2020. And the restaurant workers that kept their jobs faced higher Covid infection rates and low wages. Post-pandemic, things aren’t much better. While the Covid-19 pandemic brought workers rights to the forefront of the national discussion, the problems have been gaining interest for over a decade.

How Does this Affect Labor Rights?

Labor rights and bargaining power in the U.S. have been declining for generations, leading to a dramatic rise in economic inequality. Despite “strong employment growth in recent years,” the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found that “the portion of national income that goes to workers, known as the labor share, has fallen substantially over the past 20 years,” to historic lows.

Workers today don’t have the reliable safety nets or worker networks (such as unions) that past workers did. Thus, they are less able to risk bargaining with their employers for better pay and benefits. But the Biden administration has used its expanded federal power to change the balance between workers and employers. Expanded Unemployment Insurance and “stimulus payments,” as well as groundbreaking programs like the Child Tax Credit, can give workers the safety to seek better treatment and employment without fear.

Chew On This

The restaurant industry is a microcosm of this phenomenon. With Covid cases on the decline, restaurants around the country are eagerly opening up, hampered only by the fact that they have no workers. Restaurant owners are blaming enhanced unemployment insurance (UI) and stimulus payments, claiming workers would rather get paid to sit at home than come in to work. The National Joint Economic Committee has dismissed this view, stating that “despite UI’s measurable role in stabilizing consumption and supporting struggling households, some are claiming – without sufficient evidence – that UI benefits are suppressing reemployment.”

UI is demonstrably good for the economy and working families, and isn’t responsible for the restaurant worker shortage. In fact, it isn’t really a shortage: employers could reverse it if they paid their workers more and had better benefits. Restaurant workers are headed to other industries and those who aren’t finally have the income security to be more discerning—only accepting high-paying and safe food service work.

Why are restaurant workers suddenly changing behavior? Economists are pointing to the high number of Covid deaths in the food industry and the incredibly low tipped wage. The federal minimum wage for tipped employees is just two dollars and 13 cents, and during a pandemic, when dine-in customers are infrequent, workers can’t count on tips to supplement that. There’s good news though: the pandemic could lead to raised wages across the board, reversing the tide of wage stagnation.

Wage stagnation is when wages fail to grow at the same rate as the economy, and workers are essentially not paid the value of their labor. Wages have been stagnating in the U.S. since the 1970s, a fact many economists attribute to “labor-market concentration—too few employers competing for workers on the same level,” as explained by the Kellogg School of Management.

But for the first time in decades, thanks to restaurant worker shortages and the stability granted by enhanced UI, workers in the restaurant industry aren’t facing labor market concentration. For the first time, workers paid poverty wages can choose to go to another business paying better—or even wait for restaurants to raise their wages.

United We Stand

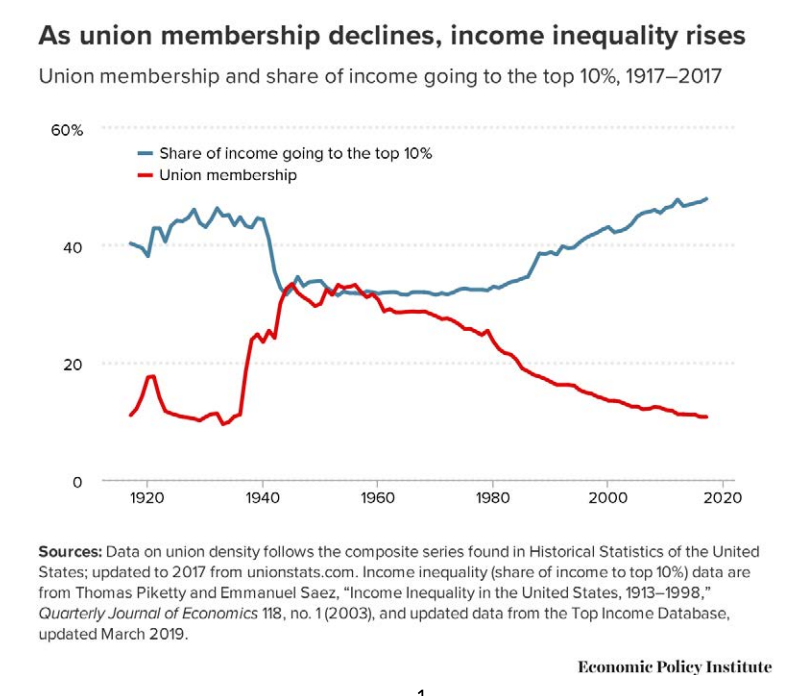

Another key factor in wage stagnation is union strength—which has been on decline in the U.S. for decades. The decline of unions is directly correlated to declining worker wages; according to the Economic Policy Institute, for the median worker, “declining unionization translates to a loss of $1.56 per hour worked, the equivalent of $3,250 for a full-time, full-year worker.”

The pandemic has caused a resurgence of interest in unions across various industries, from restaurants to healthcare. An NPR investigation into unions in the care industry cited Cass Gualvez, organizing director for Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West in California who said: “we’ve talked to workers who said, ‘I was dead set against a union five years ago, but COVID has changed that.'”

It’s anyone’s guess as to whether they will succeed—after all, threats to worker power are everywhere. A rise in union interest has been matched by a rise in union busting, such as the famous anti-union abuses by Amazon. Pressure is mounting on Biden to end enhanced UI, and some states are ending it on their own.

This new era of labor rights is a tenuous, fledgling one, reliant on the unique conditions produced by the pandemic. If corporate interests win out in this fight, we could see a quashing of the workers rights movement that lasts for decades. But if workers succeed in securing lasting rights, they could also change the economic landscape forever—only time will tell.

To learn more and support worker’s rights, explore The Groundwork Collaborative.

- Migrant Farmworkers: How Can You Get Involved? - November 30, 2021

- Migrant Farmworkers: Up Close and Personal - November 15, 2021

- Who Are Migrant Farm Workers, and What Do They Face? - November 8, 2021