Last month, I walked into the entryway of my local Walmart—and stopped. A large blue box stood next to the cart I was about to grab, with a sign telling me to recycle my old plastic bags. Not just Walmart’s bags, but any bag, from any place.

I was surprised enough to pause and take a picture. Plastic bag recycling? Growing up, I learned early on that plastic bags can’t be recycled at home; they’re a form of soft, flexible plastic that doesn’t play well with conventional recycling machines. Even if they get a second life as a small garbage bag, plastic bags generally end up in a landfill or drifting aimlessly down the street.

But I learned something new that day: it is possible to recycle flimsy plastic packaging, too. It just takes a little extra effort to find a drop-off location.

Where Does It All Go?

As we learned in last week’s Impactfull article, plastic is everywhere—in our cabinets, our oceans, and even our stomachs. Every year, we produce 300 million metric tons of plastic waste—equivalent to the weight of 900 Empire State Buildings. In order to solve our plastic problem, we’ll need to both clean up all the plastic that already exists and prevent more plastic from being disposed of in the future.

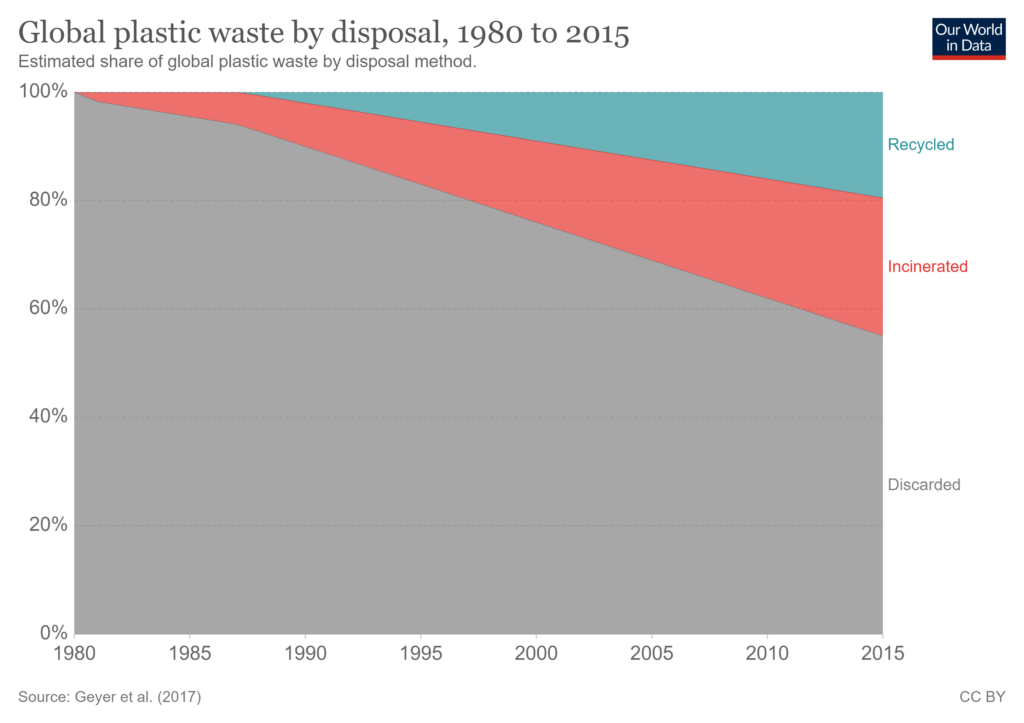

As shown above, most plastic waste ends up being discarded rather than disposed of properly—meaning it either sits in a landfill or ends up as pollution in the environment. Plastic cleanup involves both removing discarded plastic from beaches, waterways, and wherever else it serves as a pollutant, as well as disposing of it properly, ideally by recycling it.

Plastic can also be burned, along with other forms of nonhazardous waste, in an incinerator. Since the late 20th century, most incinerators in the United States have converted heat from the burning process into power for our energy grid. Instead of sitting in a landfill, plastic waste becomes a useful energy source. Critics, however, note that while incineration does remove plastic pollution, it contributes to carbon dioxide pollution. Some argue that burying plastic waste is a better alternative, as it would lock that carbon away.

But before we can recycle, burn, or bury our plastic, we have to clean it up. Sometimes, however, the initial trouble is finding it.

Hunting for Plastic

Of the 300 million metric tons of plastic waste we produce annually, an estimated 8 million metric tons flow into the ocean; some studies currently place the number as high as 11 million metric tons. But when researchers attempt to quantify the amount of plastic floating in the open ocean, they usually find significantly less than expected—what Our World In Data refers to as “the missing plastic problem.”

Theories abound as to where all of that missing plastic goes. Maybe it ends up as microplastics buried in the guts of sea creatures, or hides out on the ocean floor, out of reach of net trawlers. The following video from Vox includes another theory: most ocean plastics may linger along coastlines, rather than in the open sea.

In the meantime, researchers have come up with a creative way to look for some of that missing plastic: satellites that measure the “roughness” of the ocean surface. Plastics, and ocean debris in general, yield calmer seas because the wind can’t stir them up as easily. This new method will allow researchers to track areas with high concentrations of microplastics by examining how “rough” or “smooth” the ocean surface is, then comparing it to how it should be based on wind patterns.

Other areas with high levels of plastic are more easily identified. Several garbage patches exist in our ocean gyres (enormous, rotating currents in the ocean where plastic products have collected over the years). Lakes and rivers have also seen significant plastic accumulation in recent years.

Ocean and beach cleanup projects, in turn, work to remove plastic from these environments. But once we’ve found and collected our plastic, how do we prevent it from ending up right back in the water?

Ideally, we would recycle it. But as the past few years have shown, recycling plastic is anything but easy.

Hard to Recycle

We’ve only managed to recycle 9 percent of all the plastic waste we’ve ever produced. This is partly due to availability; recycling efforts have only been around for about half a century, and sometimes, well, the trash can is just closer.

Largely, though, this issue is the result of serious challenges in our plastic recycling system.

Plastic isn’t the best material for recycling. Substances like glass and metal can be recycled over and over again without losing functionality, making them prime candidates. Plastic, on the other hand, degrades with each trip through the recycling plant. Eventually, it becomes useless.

Furthermore, not all plastics can be recycled in the first place—including many single-use items. Those plastics that can be recycled are also subject to market demands: if no one wants the lower-quality recycled material, it won’t be recycled.

Clothing and other items made from recycled plastic bottles are also a popular trend. What’s better for an eco-friendly image than fighting pollution by turning plastic waste into fashionable clothes? My Instagram feed routinely advertises companies like Girlfriend Collective and Rothy’s, both of whom use recycled plastic bottles in their clothing, and other major brands like Patagonia have hopped on board in recent years.

Plastic-based clothing, however, comes with its own set of challenges: it sheds microplastics throughout its lifetime, and clothing is difficult to recycle when worn out. Additionally, many fabrics are a mix of natural fibers and plastic-based synthetic fibers. Separating the two for recycling purposes can prove nearly impossible.

Plastic Politics

Finally, recycling systems around the world (and especially in the United States) simply are not up to scratch. For years, countries like the United States exported their recyclables to China for processing. Faced with growing piles of contaminated and unrecyclable plastic, China banned many forms of imported waste in 2018, including several types of plastic waste.

I remember this well. Having grown up with a recycling bin in the kitchen, I was surprised when my mom stopped me from adding some of the items I was used to recycling. Our municipality had restricted what they would allow into their recycling facilities, and much of it ended up in landfills anyway. The United States’ recycling system wasn’t equipped to handle such a sharp increase in plastic waste. There was no longer a market for recycled plastic, so why bother collecting it?

Since China’s ban went into effect, investigations have found that the United States continues to export some of its plastic waste—often to countries that already aren’t equipped to handle their own waste. The rest remains in landfills or disappears into the environment.

In the end, even our best cleanup efforts don’t remove the omnipresence of plastic in our lives. We use plastic gloves to fill plastic bags with the plastic we pick up on the beach, in hopes that it ends up in a recycling plant—or even just a landfill—rather than back in the ocean it came from.

In order to permanently get rid of all our plastic waste, we’ve got a lot of cleaning up to do. And that’s just the plastic that currently exists. Next year, and every year after that, we’ll add another 900 Empire State Buildings’ worth to the mix.

To rid ourselves of our plastic problem for good, we won’t just need better recycling and cleanup efforts. We’ll need to use less of it to begin with.

This Wednesday, listen to our next podcast episode to hear my conversation with Katherine, our Nonprofits Director, about a few nonprofit organizations working to keep plastic out of our oceans. Check back here on Monday to learn about the zero-waste movement and the all-important question: how much do our individual actions matter, anyway?

- A Dose of Climate Optimism from 2021 - January 20, 2022

- When It Comes To Climate Change, Language Matters. Here’s Why. - December 28, 2021

- The EPA Wants To Take A Few Years To Regulate PFAS. Here’s Why. - October 28, 2021