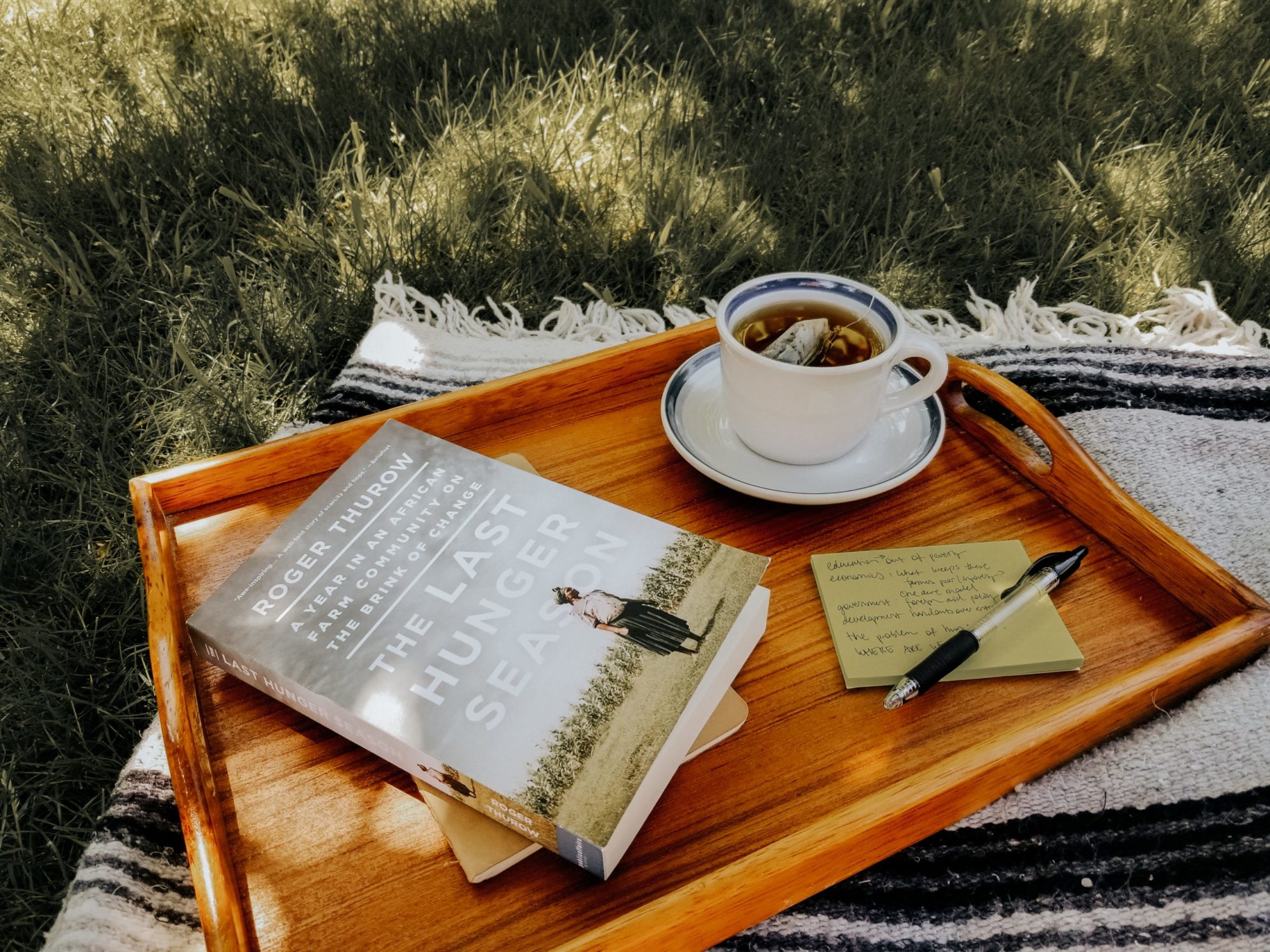

Since finishing up final exams last week, I’ve found myself with a lot more free time on my hands. To be honest, I’ve spent most of it reading books—from old middle-school favorites to some new finds recommended to me by friends. This week, I’ve been looking back through Roger Thurow’s The Last Hunger Season. Full disclosure: this book was assigned reading for a class on global inequality that I took this semester. However, I ended up enjoying it enough to keep it after the class finished up for the year, and I’m excited to share some of my takeaways from the book.

The Last Hunger Season chronicles a year in the lives of several smallholder farmers in Kenya, documenting their interactions with agricultural development programs and famine relief efforts. When I say “smallholder farmers,” think of a small, family-operated farm, one that often serves as a family’s primary source of income. Thurow paints a striking picture of the paradox of Kenya’s “hungry farmers”: at the time this book was written, the region that contributed the most to Kenya’s agricultural industry was also the country’s most malnourished and impoverished region.

How is this possible? And how does foreign aid from wealthy countries, like the United States, come into play? Here’s what I’ve learned.

The root of the problem: dependency

Revolutionary agricultural developments in the twentieth century, from fertilizer improvements and new technology to genetic modification and selective breeding, made it possible to produce massive amounts of cheap food. Unfortunately, these “revolutions” died out before they could reach Africa’s farmers; Thurow believes that they were viewed as “too poor and remote” by the agricultural industry.

As we moved into the 21st century, Thurow explains that farmers in rich countries, with agricultural developments available to them, were churning out food at incredibly low prices. It was easier for poorer countries, like Kenya, to buy that cheap food rather than produce it themselves at a lower efficiency. Famines were solved in the form of food aid programs, bringing food directly to those in need.

Hence the idea of dependency. As I progressed through the book, Thurow’s view on this point became clear: cheap food imported from rich countries made it hard for Kenya’s farmers to sell their own produce, which in turn kept them in poverty. They simply couldn’t compete.

Aid can be helpful…

As the book follows the daily lives of the smallholder farmers, Thurow also walks through the efforts of one non-governmental organization (NGO) working directly in Kenya, as well as several other countries, to bring modern agricultural developments to these small farms. The One Acre Fund is credited with working to solve hunger, not by providing food handouts, but by bringing high-quality fertilizer and seeds directly to farmers, often at a lower cost. One Acre provides training in modern planting techniques, and is often able to bargain for higher prices when the farmers sell their crops during harvest. The overall effect is evident throughout the book: many smallholder farmers saw their grain yields increase dramatically, and the promise of future bountiful harvests provided hope that farming could pave a way out of poverty, rather than keeping them trapped in it.

…until it’s not.

When faced with a drought-induced famine, the Kenyan government made the decision to import food aid from wealthy donor countries as an emergency relief measure. As Thurow observes, this “Band-Aid” solution kept people fed for the time being, but made it difficult for the One Acre farmers to sell their crops when the harvest came. There was a surplus of food, but no one was buying—even as millions of Kenyans faced hunger and starvation.

To Thurow, the solution is simple: reforming food aid to prioritize local farmers, buying local food first and only resorting to donated food if necessary. It’s a solution promoted by the farmers themselves, as well as the founder of One Acre. Agricultural development, rather than dependency, would allow Kenya’s farmers to stand on their own two feet and create an independent, successful industry, with benefits to both Kenya’s economy and food security.

“As human beings, we respond to emergency needs. But we can’t Band-Aid this problem forever. We need relief aid, but the only permanent solution to famine is permanent and sustained increases in food production. We have to invest in long-term agricultural development.”

Andrew Youn, founder of the One Acre Fund, as quoted in The Last Hunger Season

The impact of climate change

Of course, the potential impacts of climate change could have dramatic effects on Kenya’s farming industry, as well as the entire global food supply. Drought and changing weather patterns are a common theme throughout the book, and several farmers describe the effects of climate change that they’ve already begun to see: the declining frequency of the rainstorms vital to crop growth, as well as the increasing severity of the storms when they do come.

Within the past year, you’ve likely seen these effects without knowing it. The bushfires in Australia at the beginning of this year came partly as a result of a strong Indian Ocean dipole (similar to the El Niño cycle in the Pacific). A dipole, of course, has two sides, and on the opposite end from the fires in Australia was extreme rainfall and flooding in Kenya and other countries in East Africa, putting crops and lives at risk. This dipole is projected to become even stronger in a warmer climate, further increasing the risk to Kenya’s farmers and so many others.

Our world’s food supply will face many challenges in the years to come, from climate change to growing populations and a decreasing water supply. If you’re curious about how food aid works and how different groups are working to solve hunger, or if you’re looking for an engrossing, educational read for your quarantine, The Last Hunger Season is a great choice.

Want to learn more about hunger and food insecurity here in the United States? Check out Grace’s post on helping out food banks during the COVID-19 crisis.

- A Dose of Climate Optimism from 2021 - January 20, 2022

- When It Comes To Climate Change, Language Matters. Here’s Why. - December 28, 2021

- The EPA Wants To Take A Few Years To Regulate PFAS. Here’s Why. - October 28, 2021