Between harmful rhetoric about immigration and campaigns of misinformation about climate change, the world is unprepared for a dramatic increase in climate “refugees” over the coming decades. So, why “refugees” in quotes?

Under the leadership of the United Nations, the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees defines the “refugee” concept and discusses the protections afforded to such individuals. The Convention identifies five categories for recognition of refugee status. A person must hold “a well-founded fear of persecution” on the basis of: race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. International humanitarian law entitles refugees to the principle of non-refoulement, which refers to a universal protection against involuntary return to a country where a refugee has reason to fear persecution. Notably, none of these categories address climate change, and neither have most scholars who study human migration.

Until recently, violent conflicts like civil wars took precedence in academic study and journalistic treatment of refugee crises. Scholars are increasingly observing how this approach is insufficient to address shifting refugee flows. A new population is appearing at international borders, hoping to receive the same protections and rights as refugees whose identities explicitly appear in the text of the 1951 Convention. These individuals face a previously undescribed threat — hostile climate change — which threatens their homes, food sources, social communities, and even entire countries.

Why now? If we knew that climate change existed decades ago, why did it take so long to see refugees who claimed to be fleeing droughts, floods, and other catastrophic weather events? The answer is that often, refugees who claimed status under one of the five explicit categories in the 1951 Convention actually were pushed into violent conflicts by climate change. Take, for example, the 2011 Syrian civil war. A five year drought pressured rural residents to move to more populated areas, like Aleppo, where they scrambled to find resources offered by an increasingly repressive regime that brutalized resistance. Syrians fleeing the conflict often claimed refugee status because of their political protests, when climate change served as the root cause of violent conflict.

So, how will we respond to climate refugees?

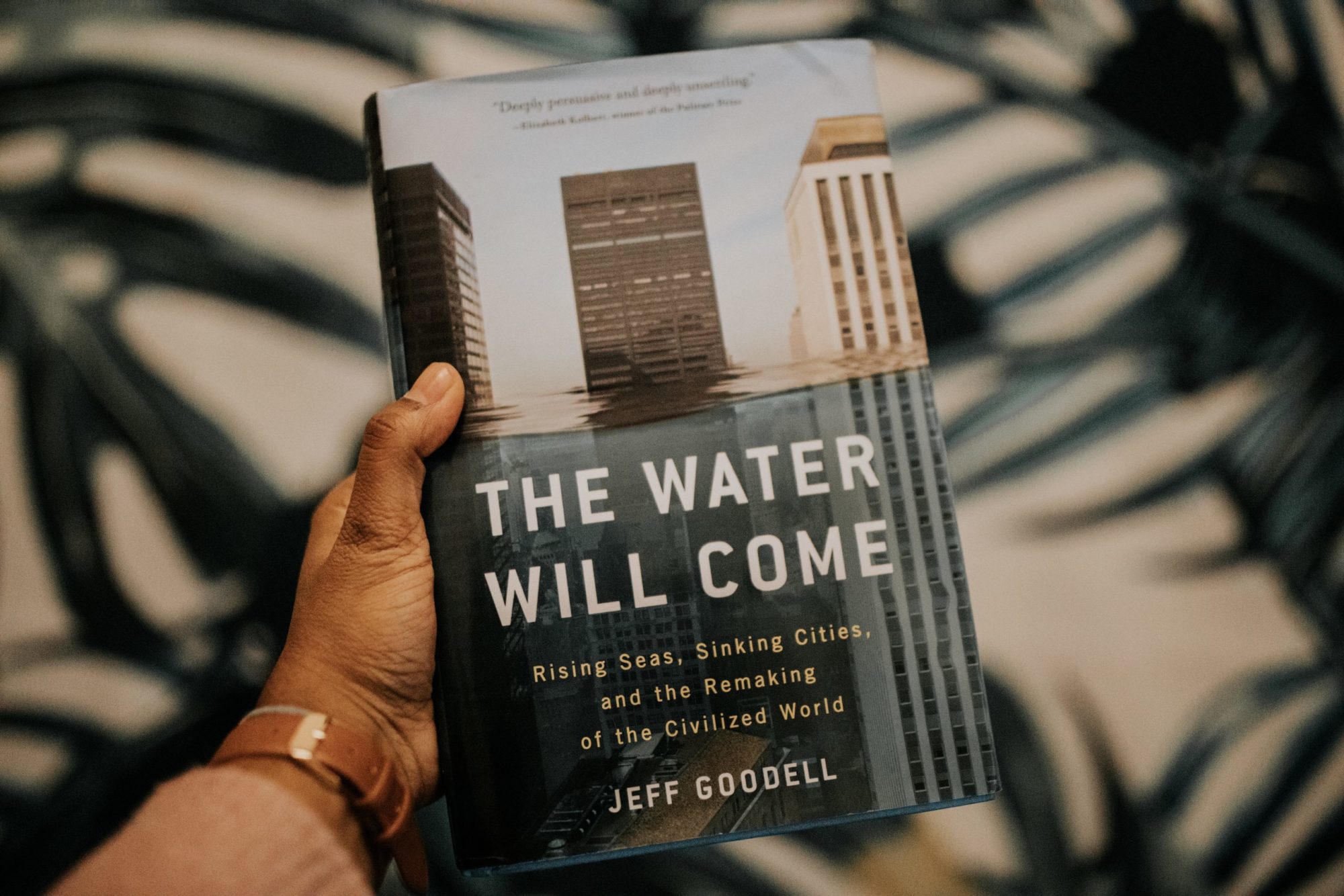

Recently, I reread the 2017 book The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World. In it, author and journalist Jeff Goodell paints a bleak image of what the world will look like in fifty or one hundred years if no action is taken against climate change — complete with an underwater Atlantis of Miami, massive walls to protect wealthy cities, racial and socioeconomic climate apartheid, and of course, millions of vulnerable climate refugees. The depressing image painted in this book made me question whether my choices to adopt a vegetarian diet, practice recycling, and reduce my consumption even made a difference.

Beyond calling attention to these impending challenges, Goodell also offers great prescriptions for how to overcome so-called “climate anxiety,” and actively work toward climate solutions that could improve the lives of countless refugees, both now and in the future. By the end of the book, I felt both more hopeful and less alone. Our individual contributions, while still small, can generate massive change when effectively mobilized together and exercised in tandem with political activism.

Am I entirely pessimistic? No, and in fact I think there are several bright spots to consider in the world of refugee studies. In places ranging from Virginia to New Zealand, activists, politicians, and refugees themselves are mobilizing together to plan for climate change in the future and address temporary solutions for resettlement in the present. Most recently, the United Nations Human Rights Committee ruled in a landmark judgment that a member state will violate its human rights commitments if, “it returns someone to a country where — due to the climate crisis — their life is at risk, or in danger of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment triggered.” This judgment uses language so similar to that of the principle of non-refoulement that it is difficult not to see this as an endorsement of climate refugees as legitimate asylum-seekers.

While we are on the way toward more tenable solutions to the climate refugee crisis, we are also stalling. Until we remove the quotation marks from our language and actively recognize that forced migration due to the climate deserves the same explicit protection afforded to other categories for refugee status, we hinder ourselves from the difficult conversations about how to provide the best care for refugee populations. We must vocally acknowledge and advocate for climate refugees in our own communities and across the world.

It is time to see climate refugees for who they are, and to develop equitable and just ways to protect them accordingly. As individuals, we can work toward this goal by supporting the work of organizations like the Environmental Justice Foundation and voting for candidates who champion ethical refugee policies.

- State of the UNIONS: Welcome to September’s Impactfull Series - September 2, 2022

- What We Can Learn from the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis - March 29, 2022

- The Olympic Effect: Changes in Host Communities - February 21, 2022

Pingback: Misconceptions About Immigration – Novel Hand