Like many college students, I can admit that I have a somewhat personal relationship with coffee. Now that we’ve been taking courses online for nearly a year, I’ll reminisce with friends about little moments of on-campus life: the convenience of always-hot dining hall coffee, the routine of picking up a latte in the library cafe, or the comfort of catching up with a friend over coffee and a walk. Because I drink it often–if not most days–I figured delving into the intersection of humanitarian issues and the coffee industry would be a great way to wrap up my time as an intern with Novel Hand. When I first began researching and connecting with professionals in the field, it quickly became clear that I hardly knew anything at all about where my coffee comes from or who makes it possible for me to enjoy a cup before class in the mornings.

The reality is that over 125 million laborers and farmers across the world, from countries like Brazil to Ethiopia to Vietnam, depend on the coffee industry for their livelihoods. Competitive global prices for labor prevent many farms from profiting off of their produce, and because most coffee labor is seasonal, it’s easy for producers to exploit and mistreat their workers. Laborers may be offered inadequate housing, refused benefits, or given lowered wages, which forces laborers to bring their children to work in order to meet daily quotas—and the challenges don’t stop there.

Humanitarian Issues Within the Coffee Industry

Hanes Motsinger is the Social Innovation Program Manager at the Wond’ry, Vanderbilt’s center for innovation and design. Here, students, faculty, and staff can create and try out ideas for new inventions and business models that focus on social impact and social innovation. Through these inventions and models, students and faculty work together to understand and solve the most complicated challenges that face our communities: climate change, housing, food insecurity, and more. Most recently, Motsinger has been a key player in creating the Wond’ry’s brand new Coffee Equity Lab. Its mission is to both provide students with experiential learning opportunities where they can engage with global issues through the lens of coffee and to engage the greater Vanderbilt community with projects that advance equity and sustainability in the sector.

When I asked about the most significant humanitarian issues currently facing the coffee industry, Motsinger was quick to note that there are many.

“When you’re dealing with a global industry, it’s inevitable that there will be a number of challenges. Right now,” she told me, “on the farming side, there’s a concern with child labor and a concern with indentured or slave labor in some countries where seasonal farmworkers are promised payment and don’t get paid. They’re promised meals for themselves and their families and then don’t get fed.”

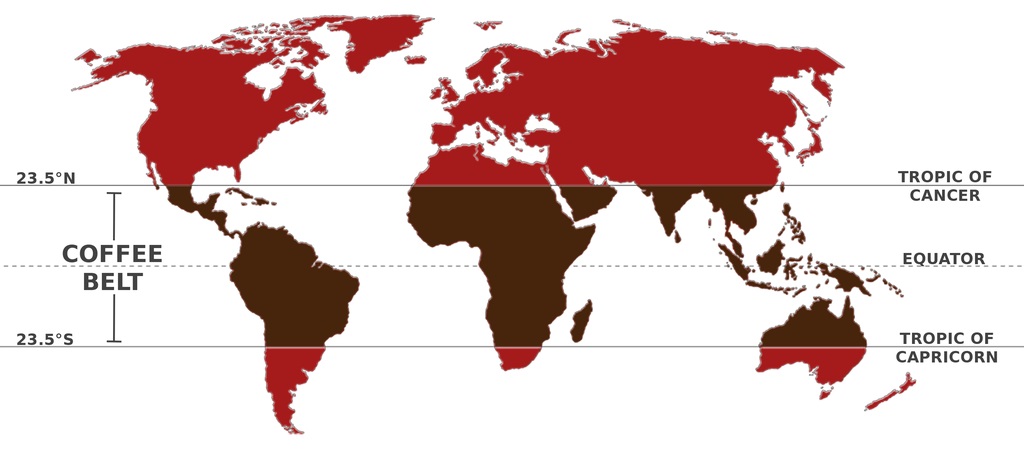

She explained that the exploitative labor practices can be especially hard to pinpoint because the industry is so dispersed. Most coffee is grown by tiny farms across the equatorial and subtropical countries of the world. This is known as the Coffee Belt or the Bean Belt. These regions have the right climate and altitude for coffee, but oftentimes they are also developing countries, and many coffee farms are small, unregulated, and rural.

Along with labor concerns, gender equity is another huge humanitarian issue in the coffee industry. I was surprised to learn that women are responsible for the majority of coffee farm labor, but they don’t have equal access to credit resources. Women are largely unable to grow their own farms because they aren’t able to purchase land or start businesses in the way their male counterparts can.

Motsinger also emphasized that, in the United States and abroad, racial inequity is another significant issue facing the sector. Typically, people of color and racial minorities in the coffee industry don’t seem to have the same upward mobility as their white counterparts. Oftentimes, they’re also paid less. When consumers approach people of color and racial minorities working in the industry, they do so in a very different way compared to how they might approach white individuals in the industry.

Regardless, it’s not all negative. Because the industry is so wide-spread, achieving industry-wide, lasting change takes a huge amount of time and coordination, but Mostinger assured me that, slowly but surely, “progress is being made in all of these areas.”

Certification Regimes

One of the most significant ways the coffee industry has been becoming more economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable is through certification regimes. You might be familiar with Fair Trade and the Rainforest Alliance, or even Smithsonian Zoo’s Bird Friendly.

So how do certifications work? If a farmer, producer, or cooperative decides to abide by a specific set of sustainability regulations, they can invest in a certification, which promises a 30-cent premium over market price. Unfortunately, it’s the farmers and producers themselves who incur the cost of the pricey certification, and since there’s currently an over-saturation of certification in the market, many certified coffees must be sold at market price, meaning farmers and producers aren’t able to reap the financial benefit of their investment. Still, the market for coffee is volatile, and when it drops especially low, certifications provide a safety net for the producers behind them.

Over recent decades, there’s been an explosion in certification regimes, leading to a growth in consumer skepticism that’s prompted individuals to ask themselves whether they’re being “green-washed.” That is, do the numerous labels, badges, and certifications on our coffee make that much of a real-world difference, or are they only making consumers feel as though the brands and companies they purchase from are ethical and sustainable?

Though they’re imperfect, Hanes Motsinger noted that certifications really do benefit the industry. She recalled that Kim Elena Ionescu, Chief Sustainability Officer of the Specialty Coffee Association, once told her that, without certifications, the coffee industry wouldn’t be anywhere close to where they are today—a beacon of hope for sustainability.

First, Second, and Third Wave Coffee

Dr. Ted Fischer, an author, department-head, and anthropology professor at Vanderbilt, has dedicated the last decade of his career to researching coffee, and he attributes this decision to his own personal relationship with the beverage. When I chatted with him about his research, Fischer brought me back to his time as a graduate student in New Orleans, where he’d spend days doing work in PJ’s Coffee on Magazine Street, noticing that customers ranged from police officers to young students from the school down the street. He quickly realized the scope of lives that coffee affected. As a result of the culmination of those early experiences, his time in Guatemala, and the fact that “a lot of anthropology is serendipity,” Fischer has ended up an expert on the coffee industry—specifically, high-end, third wave coffee.

There are three waves—or categories—of coffee, which are determined by quality. The first is, naturally, first wave coffee, which began in the mid-20th century. First wave coffees are mass produced and generally grown on big plantations. Fischer encouraged me to consider first wave coffees as the McDonald’s-type conglomerates of coffee, like Folgers and Maxwell House. They’re not high quality, but they are solid and reliable. Though labor practices and regulations have changed over the years, Fischer noted that, when he was in college, first wave coffee production was the “poster child” for the worst kind of neocolonial exploitation: underpaid and mistreated seasonal labor for a bulk commodity consumed by Westerners.

The second wave of coffee can be traced back to Peet’s Coffee in the Pacific Northwest, and it developed from the 1960s through the 1990s. Local roasters concerned with the quality of their coffee began popping up, and Starbucks eventually took this sentiment global. Certifications also began to emerge at this time.

Third wave coffee is now taking the idea of sustainable, quality coffee to the next level. Many producers, Fischer noted, now strive to make their coffee as unique and specialized as possible through small micro-lots, unusual single-farm varieties, and strange, innovative new processing methods. Third wave consumers want direct relationships with coffee growers, and brands will often tell the stories of farmers and the history of the land they grow on. Although the most sustainable option, third wave coffees can border on exclusivity; they sometimes sell for extremely high prices.

How We Can Make an Impact

According to Hanes Motsinger, “Coffee is too cheap.” Since coffee is priced on a commodity market, prices have been kept especially low; many would consider a five-dollar cup of black coffee to be expensive. Motsinger wants people to understand that coffee truly is a luxury. The process of harvesting and roasting coffee consists of painstakingly labor-intensive steps. First, coffee cherries are picked by hand, and since they ripen at different speeds, individuals must come back to the same trees day after day during harvest season to continue selecting only the ripe cherries. Beans then have to be sorted by hand, de-pulped, and dried in a multi-day process wherein laborers turn them over with rakes. Finally, they’re milled, and quality beans are hand-selected by an assembly line. Fischer explained, “If you worked on a coffee field for a day, you’d pay fifty dollars for a pound of coffee. So much labor goes into one cup of coffee, it’s remarkable.”

Buying directly from specialty coffee producers can also make a huge impact on the lives of laborers and growers across the globe. “Direct Trade, Better Than Fair Trade,” is the motto of Cafe Juan Ana Coffee in San Lucas Toliman, Guatemala. Their Direct Trade Model, wherein consumers buy bags of specialty coffee directly from their site, “ensures that the grower receives the most for their labor.”

I connected with Edy Morales, a San Lucas Toliman local who has been director of Cafe Juan Ana’s coffee program since 2015. Harvesting season runs from December through March, and during that time, Morales works eight-hour days where his responsibilities lie in all areas of the program, from coffee processing and roasting to export quality and packaging.

With the help of a translator, Morales told me that the most rewarding part of his job is knowing that he has a stable income to provide for his wife and two children and also knowing that he can support small growers in his community. He wants consumers to know that, by purchasing from Cafe Juan Ana, their money goes directly toward supporting families and producers in San Lucas Toliman. At the same time, consumers will be receiving a 16-oz bag of high-altitude specialty coffee for only $10.

Although we don’t always have the time or money to spend on specialty coffee, we can still make the decision to be informed consumers. A lot can be deduced from the websites of different roasters and coffee shops, such as how they source their coffee and what importers and farmers they work with. They might have information about how they pay their farmers or what those relationships look like.

Hanes Motsinger also encourages consumers to chat with their baristas. At a local coffee shop, the person at the counter should be able to tell you a bit about sourcing practices and policies. There’s also no reason to stop going to Starbucks. Simply take the time to read up on some of their steps toward sustainability. Arguably, when Starbucks makes even the smallest change toward ethical and sustainable practices, it makes a huge difference in the lives of coffee workers across the globe.

Since so much of modern consumption is complicated, it can be difficult to really delve into research for everything we buy, and that’s where consumer shorthand comes into play. If you’re purchasing coffee and have the option between certified and non-certified, always go for certified, which, though imperfect, will have at least some standard of environmental, economic, and social accountability.

Ultimately, taking the action to be an informed consumer and sharing what you learn with others makes an impact. Coffee touches hundreds of millions of lives, and it’s both important and powerful to understand who makes our morning coffee.

“If we don’t pay attention to that, we won’t be drinking much good coffee in fifty years,” Hanes Motsinger told me. “It’s just good to care.”

Resources for Learning More

- Look into and support companies who participate in initiatives and organizations like the Sustainable Coffee Challenge.

- Use the internet to explore small-scale specialty coffee producers across the globe, and make a purchase or two directly from a specialty grower like Juan Ana Coffee! Maybe you’ll find a new favorite roast and make a new connection along the way.

- Check out the economic, social, and environmental practices of big names like Starbucks, Dunkin, and Costa.

- Google your local coffee shops or talk with baristas to determine which options are the most ethical and sustainable, and share what you learn with friends and classmates.

- To learn more about climate change’s impact on coffee growers, read Sydney’s Novel Hand article, “Climate Migration: A Crisis of Coffee in Guatemala.”

- Take just three minutes to listen to Novel Hand’s bite-sized Activism, Meet Impact podcast episode, An Ethical Cup of Joe.

- Check out Novel Hand’s Listenable course, The Humanitarian Side of Everything, which has a lesson dedicated to coffee and chocolate.

- Consuming Sustainably and Buying Direct: Humanitarian Issues and Impact in the Coffee Industry - February 1, 2021

- The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: What’s Happening with Oil and Gas Development in Alaska - November 23, 2020

- Artificial Intelligence and Discrimination: Where Bias Meets Tech - November 9, 2020