On July 14, the U.S. rescinded the ICE policy that would have required international students to leave the U.S. and lose their visas if their university was entirely online. After a whole week of constant panic, frantic emails and contingency planning, I could finally breathe a sigh of relief. Even though I am going back to a country with the highest COVID-19 case count in the world, at least I will not be deported if the one in-person class – out of five – that I am taking goes online. This victory for international students was only possible because American institutions immediately rallied for us – nine lawsuits were filed challenging the policy, with the most prominent one, filed by Harvard and MIT, being backed by 200 universities.

But undocumented immigrants do not get the same support. As we celebrate this win, it is imperative to include Dreamers, immigrants detained at the border, immigrants torn apart from their families and hardworking immigrants who live in constant fear of deportation in our fight for justice.

ICE: Getting the Complete Picture

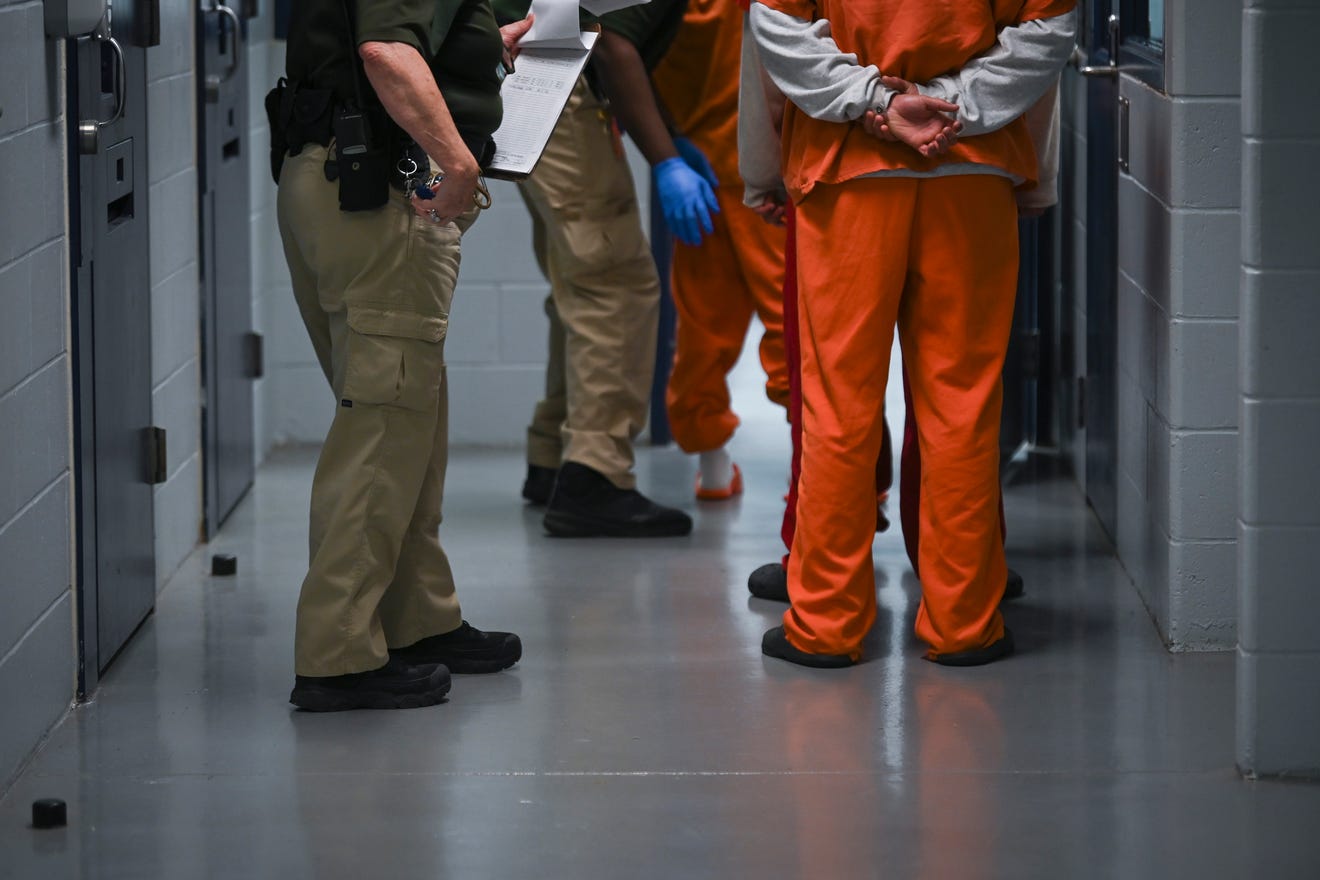

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, was created in 2003 as a subsidiary of the Department of Homeland Security. As described by the Department of Justice in 2004, the primary mission of ICE is to “prevent acts of terrorism by targeting the people, money, and materials that support terrorist and criminal activities.” On its own, the existence of ICE made little sense. In 2005, the Inspector General of the DHS said in a report – “We could not find any documentation that fully explains the rationale and purpose behind ICE’s composition.” Since ICE did not serve a purpose large enough to justify its institutional existence, the agency was sized up in the coming years by finding crime where there was none. A quota of detainees, in essence, was established for ICE agents to catch, when Congress increased ICE funding in 2009 based on the number of beds occupied. Today, ICE is required to maintain 40,000 beds worth of detainees. People are being detained for profit – the major beneficiaries of ICE’s detention centers are private corporations such as CoreCivic and GEO. In 2018, CoreCivic and GEO derived 25% and 20% of their profits from ICE, which is their biggest client.

Originally tasked with tracking transnational terrorism and crime, ICE now arrests, detains and deports hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants. In 2019, ICE detained 510,854 people, and deported over 267,000 people. The average stay in a detention center is four weeks, although some have remained in detention for years. On any given day, there are 2000 unaccompanied children in ICE custody. By law, these children should not be kept in ICE detention centers for more than 72 hours; they are meant to be sent to Health and Human Services, which then finds the child a sponsor to house the child. This, however, is not happening – children are being held for several days before being sent to the HHS. There have been reports of medical neglect, physical and sexual abuse, as well as unhygienic conditions inside detention centers. Teenagers in ICE custody, who are detained in relatively safe shelters run by the Department of Health and Human Services, are being “aged out” until their 18th birthdays, upon which they are transferred to ICE’s adult detention centers.

Detention During Coronavirus

The unhygienic conditions and small, confined spaces in detention centers spell disaster in the time of COVID-19. More than 3000 immigrants in ICE custody have tested positive for the coronavirus, and 1000 detention center employees have also tested positive. Immigrants have tested positive at the alarming rate of 50% of all those tested, an extraordinarily high percentage. There have been reports of rationing of Personal Protective Equipment kits, delayed and inadequate testing, as well as unsanitary conditions within the detention centers.

Citing the coronavirus, a federal judge, U.S. Judge Dolly Gee, has given ICE a July 17 deadline to release all minors who have been in the agency’s custody for over 20 days. ICE now faces the choice to separate families and release the children without their parents, or to release a parent with the children. Parents have to choose between separation from their children or prolonged detention for their children in hazardous conditions – during a pandemic. Many of these immigrants are fleeing from violence and war in their native countries, and are stuck between a rock and a hard place when choosing between separation from their child, or the detention and possible deportation of their child to the violence they were fleeing.

Call to Action

Our fight for justice has only begun with the international students getting some relief. We must do away with the harmful idea of the “good” or “ideal” immigrant as the only one worthy of our support and advocacy. No human being is illegal; no human being should have to choose between disease in the U.S. and violence in their home country. We must keep pressuring the administration as we did when international students were at risk. Several human rights and immigrant rights groups have petitioned the government to release all detainees in sight of the pandemic; this Amnesty USA web page cites useful resources for citizens to join the fight. It includes a social media toolkit, as well as email forms to be sent to governors of U.S. states, asking them to pressurize ICE to release detainees. Let’s do our part in protecting some of our most vulnerable populations; they need our support now more than ever.