The United States Immigration system can be likened to a Hydra, with a different issue, policy, or loophole at each head. Each time an issue seems to be grasped, five more pop up in its place. Far too complex to try and tackle in one piece, U.S. immigration is multifaceted, decades old, and inexplicably intricate.

Here, I examine several major recent issues in the U.S. immigration system, specifically focusing on asylum seekers at the southern border. Through the examination of the system’s problems, I will offer plausible solutions.

In recent years, activists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), politicians, and news sources have claimed that the U.S. Immigration system is broken. The Cato Institute, an American think tank, identifies 26 reasons why the legal immigration system is in disrepair. These reasons range from the overall stagnant nature of the system, to citizenship wait-times, to the virtually unrestrained authority of the president over immigrants.

When asked if the U.S. immigration system was “broken,” former diplomat and now immigration lawyer Chris Richardson said, “It’s not that it’s broken, it’s just that it’s outdated.”

Richardson then went on to explain that much of U.S. immigration law today revolves around the philosophy behind the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act. This act, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, targeted Jews, communists, South-Asian immigrants, and a variety of other “undesirables.” Those who wrote the act were quite conservative and racist, seeking to admit individuals with a “similarity of cultural background” — namely European whites. Richardson explained that this act and its successors were built in a “world that doesn’t exist anymore.” Thus, he explains, it isn’t necessarily that the U.S. immigration system is broken, it is just outdated, and, according to Richardson, it is set up in such a way that makes it challenging to update.

Exclusion Ingrained: A Brief History of U.S. Immigration Law

As described above, the immigration system is hopelessly complex. Before diving into the issues of today, let’s take a look at how we got here. For holding the title of “the nation of immigrants,” the United States has proved to be ironically exclusionary. The first act defining the recipients of citizenship was the Naturalization Act of 1790. Those who qualified to be citizens had to be free white men of “good character.” Women, indentured servants, and slaves were excluded, as they were considered property. Thus, the origins for the U.S. admission to citizenship are rooted in slavery and coverture. White landowners did not want slaves to have any kind of legal representation and the best way to do this was to deny citizenship outright.

By 1882, the subtly-named Chinese Exclusion Act was passed to stifle the flow of Chinese individuals migrating to the western U.S. A decade later in 1892, Ellis Island opened, allowing an unprecedented influx of immigrants. With mass migration from an unstable Europe, the U.S. adopted over 12 million new citizens from 1892 to 1954, frustrating nativist politicians. Next, the Emergency Quota Law of 1921 was formed in response to WWI. This was the first time quotas were employed to limit the number of immigrants into the U.S.. The law retained that only three percent of the total population of any given country would have access to U.S. citizenship annually. This built the foundations for the Immigration Act of 1924, which capped overall immigration at 150,000 individuals per year.

Following WWII, Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, finally authorizing refugees and asylum seekers in the U.S. However, as in previous immigration practices, Catholics and those of Northern European descent were favored. This law was temporary, and refugee status relied completely on federal agents who were designated to judge the applicant’s “character, history, and eligibility.” This loophole allowed for vast discrimination to occur, as acceptance as a refugee or an asylee relied on the shoulders of the immigraiton officer. Attaining refugee status became a subjective matter.

In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act was passed. This act reaffirmed the quota system, and called for the immediate deportation of any communist, anarchist, or anti-American “aliens,” or non-citizens. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 undercut the existing quota system, which created certain allotments for each country. This act, which is largely used today, prioritizes immigrant admission into groups. Of the 170,000 admitted each fiscal year, 75 percent attempt to achieve family reunification, 20 percent towards employment, and 5 percent for refugee status. However, it is important to acknowledge that the employment allotment only permits “skilled” laborers, excluding those working in agriculture, construction, or domestic work. This closes the doors to poorer countries whose citizens may not have access to higher education, and thus “skilled labor.”

In terms of the development of refugee legislation, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees issued a protocol in 1967 prohibiting “refoulement,” or the practice of forcing a refugee to return to a country where they face imminent danger. The U.S. responded with the Refugee Act of 1980, raising the refugee ceiling to 50,000, and giving more power to the executive branch in regulating the cap. It also changed the definition of a refugee to a person with a “well-founded fear of persecution” to adhere to UN standards.

In 1986, the tides turned. To combat the growing number of unauthorized immigrants, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). This made it illegal to hire “aliens,” increased Border Patrol operations by 50 percent, and made “legalized aliens” ineligible for many federal programs. It simultaneously offered amnesty, or pardon, to unauthorized immigrants with proof of residence in the U.S. prior to Jan. 1, 1982. Ultimately, this was an attempt to disincentivize prospective migrants, making the U.S. less appealing with stricter rules. For more detailed timelines of immigration law, click here or here.

The Impact of 9/11

With the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the attitude of the United States toward immigrants shifted. Once protectionist, and with a goal of safeguarding U.S. jobs, federal benefits, and the economy, the attitude turned vastly more xenophobic and racist. The conception became that foreigners, especially foreign people of color, were potential terrorists.

In the wake of 9/11, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was formed, creating three new federal agencies: Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). According to the official DHS website, the CBP targets drugs, weapons and “inadmissible persons,” ICE “enforces criminal and civil laws governing border control,” and the USCIS focuses on “lawful immigration” and naturalization of new citizens. The formation of these new agencies sparked stricter visa regulations, biometric information collection (fingerprints and photographs), and dramatically increased staff and funding. Although its goal was to maintain national security and intercept subsequent terrorist efforts, post-9/11 immigration policy changes have been criticized for facilitating the tracking and removal of non-threatening unauthorized immigrants.

Check out this fact sheet outlining major changes in post-9/11 policy.

Check out Emma’s article to learn more about the current path to immigrant naturalization.

Where we are today

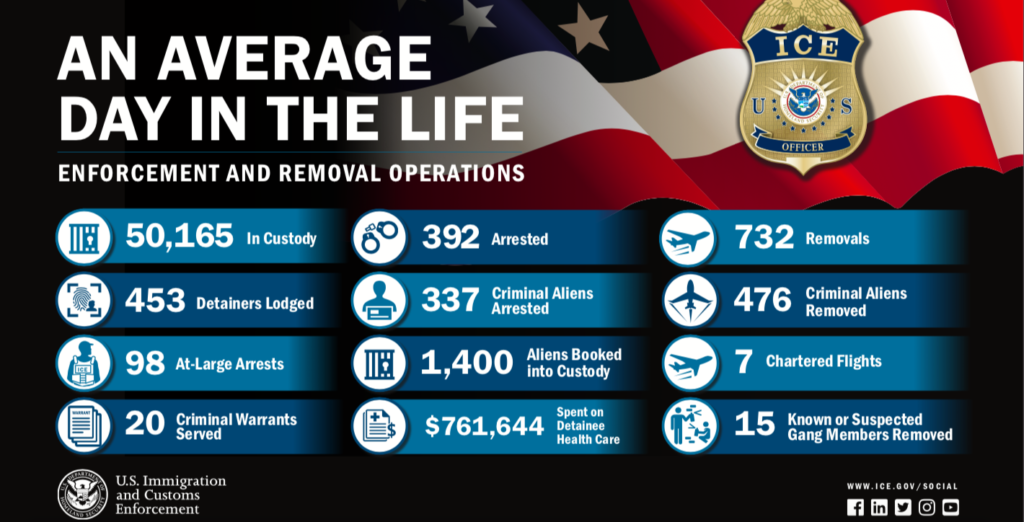

Through this perspective on the roots of immigration in the U.S., we can better evaluate the issues of today. With huge amounts of technology, funding and personnel, as well as a common philosophy that lauds stifling immigration, agencies such as ICE and the CBP take pride in numbers. The figure below for example is displayed on the ICE website. This “average day in the life” is based on numbers taken from the 2019 fiscal year.

What these numbers don’t reflect are the more horrifying metrics of a humanitarian crisis happening within United States borders.

Implications of Detention

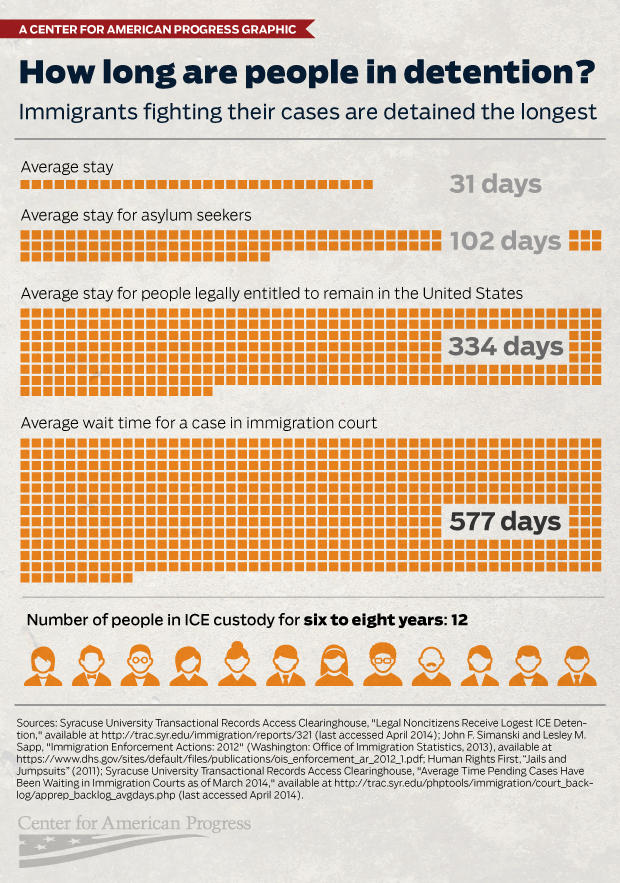

As seen above, in 2019 alone, 143,000 “aliens” were arrested, and more than 267,000 were removed. The amount of people turned away at the border increased by 68 percent, many of whom were seeking asylum in the U.S. Those within U.S. borders are consistently detained, and held in horrible conditions for months on end. With a failing immigration justice system, ICE holds individuals, “guilty” or not, in detention centers while they await their trial date. However, There are 69 immigration courts in the United States, 350 judges, and 733,365 pending immigration cases. This means that each judge has an average of 2,000 backlogged cases, causing elongated wait times in detention centers. Chris Richardson said in his interview that during his time in the U.S. State Department, he had been to prisons all over the world. After touring some immigrant detention centers in the U.S., he explained that they were as bad or worse than many prisons internationally.

Year-long wait times and poor living conditions alone are a vast breach of human rights. However, considering the more immediate human rights violations being performed elsewhere, it is challenging for activist groups to take on the long-term battle of legislative reform.

The Obstacles to Asylum

Although there are plenty of pressing issues in current immigration policy and U.S. conduct ranging from Trump’s 2017 “Muslim Ban” to a massive increase of targeted ICE raids in schools and workplaces, here I focus primarily on individuals seeking asylum and the injustices surrounding this process.

First, let’s define terms.

According to Amnesty International, while there is no internationally accepted term, a migrant is an individual staying outside their country of origin who is not a refugee or an asylum-seeker. Their motives for migration could range from work, family, or school, to natural disasters, political unrest, or poverty.

A refugee is an individual who has fled their home country as they are at serious risk of human rights violations. They are classified as a person who is at persistent risk of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Refugees have a right to international protection, and are legally recognized as such.

An asylum-seeker is an individual who is seeking refugee status, but has not yet been legally recognized as a refugee. These individuals can either be at the border or already within the state. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, seeking asylum is a basic human right, and should not be denied. Asylum-seekers may apply to be legally recognized either at a port of entry, or after they are already within the United States.

In order to be granted refugee status, one must apply and be screened, interviewed, and vetted by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The USCIS has the complete authority to determine eligibility, meaning it is a totally discretionary and subjective process. The individual eligibility officer chooses whether or not to grant refugee status to the applicant.

Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) officers often abide by their own rules, screening individuals quickly in order to process as many individuals as possible. Asylum-seekers must either prove “credible fear” or “reasonable fear” of persecution or torture within the country they are fleeing. If the CBP officer denies asylum, the individual will be referred to an immigration court for removal proceedings. Individuals may also appeal this decision to an immigration judge, but will be detained in the process, and as mentioned above, it could take up to multiple years to receive a court date.

Additionally, the vetting process is incredibly long. As of Sept. 2019 there were 339,856 pending asylum cases with the USCIS. It could take up to four years to receive an interview, and another two to four years to resolve the case. If it is denied, it can take years to receive a court date, all to potentially face deportation. This is one compelling reason that so many individuals decide not to seek naturalization. If an individual is undocumented within the United States, applies for asylum only to be denied and deported six to eight years later, it seems much more logical to opt out of any application at all. This could account for why, as of 2017, there were upwards of 10.5 million undocumented individuals in the United States; with such a complex, long, and potentially dangerous system, many may choose to remain undocumented.

While asylum seekers already in the country are granted the right to remain in the U.S. during their application process, the government has also maintained that it has the right to detain these individuals. As previously mentioned, U.S. detention centers are similar to prisons; in some cases the buildings are prisons that have been repurposed. Asylum-seekers are often called the “most vulnerable members of society.” They are children, single mothers, victims of abuse, and individuals fleeing domestic abuse or torture. To then imprison these individuals as they wait out a seemingly interminable approval process is inhumane.

Take a look at this “training module” to see how eligibility officers are guided to making their decisions.

Check out this article by Sydney for a more detailed explanation of the difference between migrant, asylum seeker, and refugee. To learn more about the asylum system in the U.S., read this article by Shareen.

Remain in Mexico

To add on to the high stress of this process, in Jan. 2019, the Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP) was passed by the Trump administration. Also known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, this protocol allows CBP officers to turn asylum-seekers away, forcing them to remain in Mexico as their cases are adjudicated. This allows for huge extrajudicial work arounds; if these individuals are not on U.S. soil, the U.S. is not legally liable for any harm that comes to them. It also often bypasses requirements to offer migrants legal assistance, as they are not within U.S. borders.

Former Secretary of Homeland Security Kristjen M. Nielsen stated that this program would “address the humanitarian and security crisis at our southern border.” The goal of the MPP, according to the Department of Homeland Security, is to decrease the amount of individuals taking advantage of the U.S. immigration system, and therefore allow more resources to go to those who legitimately need it.

However, by sidestepping one supposed humanitarian crisis, the United States has created another. Those asked to “await a determination in Mexico” are said to receive “appropriate humanitarian protections” according to the DHS, but the current conditions are far from sufficient. The majority of these asylum-seekers are living in tents, with few clothes and little food. Criminal organizations run many of these camps, kidnapping migrants, sexually assaulting them, and extorting them. COVID-19 has ravaged the camps, not only with illness, but with an increase in violence and homicide. Children are not in school, and parents are unable to attain Mexican work visas; they can only wait. As of Oct. 2020, over 60,000 asylum seekers are waiting at the southern border for their cases to be processed, which could take years. Many have been living in these conditions for more than a year. To make matters worse, Mexico is undergoing a security crisis, experiencing the highest levels of homicide in 2018 since the country began keeping records in 1997.

ACLU journalist Ashoka Mukpo visited the camps in northern Mexico in Oct. 2020 and wrote a detailed report. His takeaway was simple: “There is – right now, at this very moment – a humanitarian crisis unfolding at our southern border. And we are not paying enough attention to it.”Isn’t this in direct opposition to the idea of “non-refoulement”? To review, non-refoulement prevents states from forcing individuals to return to a place of risk. The UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights explains:

“The prohibition of refoulement under international human rights law applies to any form of removal or transfer of persons, regardless of their status, where there are substantial grounds for believing that the returnee would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return on account of torture, ill-treatment or other serious breaches of human rights obligations.”

It would seem that the situation at the U.S. southern border would qualify as U.S. refoulement; individuals are being “transferred” into hostile situations where they are in known danger of kidnapping, disease, gang violence, and other violations. This is not lost on many activist groups. Human Rights Watch encouraged the U.S. to conduct an internal investigation in June 2020, and multiple groups have brought this issue to court. Activist groups fighting for asylum rights, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), filed a lawsuit on behalf of 11 asylum-seekers that won in the lower courts, succeeding in enacting a preliminary injunction to stop the MPP process. However, the case has been appealed by the U.S. government, and the Ninth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals has given the U.S. an “emergency stay” allowing them to resume. The Supreme Court will hear this case sometime in early 2021; in the meantime, the U.S. government will continue with its current practices.

The Ice Boxes

Although this humanitarian crisis occurs right on the doorstep of the United States, there is one occurring well within its borders as well. Immigration holding cells are securitized units where individuals are kept after their arrest for a short period of time before being transferred to a detention center. These cells have been dubbed “ice boxes,” “hieleras,” or “freezers,” as they are held at extremely cold temperatures.

In an investigative report conducted by Human Rights Watch in Feb. 2018, 110 women and children in ICE detention centers were interviewed that had spent time in CBP holding cells. The report showed that these women and children were held at extremely cold temperatures for multiple nights. They were not provided with a shower for up to four days, and were not given soap to wash their hands with before and after using the restroom or eating. They were not provided with essential materials such as menstrual products or diapers for their children, and children were often separated from their parents and held separately. Finally, these individuals were often encouraged to sign papers in English that they did not understand, or to sign deportation papers after CBP officers explained that they had no chance of entering the country. Additionally, in ICE detention centers, there have been countless reports of sexual abuse, as well as a recent whistleblower claim that multiple women have undergone unnecessary hysterectomies.

One issue that can help to explain some of these injustices is that many of these centers are privately owned. The owners have a financial incentive to keep their detention centers full, and spend the lowest amount possible on its occupants. The GEO group, an investor in private prisons and ICE contractor, reportedly received 184 million in American taxpayer dollars in 2017. These private investors have no reason financially to create healthy, safe environments, thus creating horrible living conditions for those detained.

Keeping it in perspective

I believe it is important to acknowledge the function of strict border control. It is important to have a vetting system for those entering the U.S. There are criminals, smugglers, and human traffickers crossing the border. There are people taking advantage of the asylum system, who are lying or abusing these opportunities. But by no means can this be said to be the majority of people. To turn masses of abused and distraught individuals away only for them to suffer more abuse is criminal.

It is also important to acknowledge the multifaceted origins of this issue. Immigration policy such as the MPP is not novel, and cannot only be attributed to President Trump. We must keep in mind that U.S. immigration history contains an underlying goal to keep “undesirables” at bay. Although it is easy to use particular individuals as a scapegoat, or to only consider immediate issues, it is vital to keep history in mind. President George W. Bush conducted massive ICE raids, deporting unprecedented numbers of people. President Obama, often thought of as a virtuous liberal, created the “cages” or “ICE boxes” that are now condemned and developed a “No-Release Policy,” detaining families and largely refusing to release them on bond. During Obama’s time in office, nearly 3 million immigrants were deported over the course of eight years. To expect that a change of leadership will change the trajectory of immigration policy in the United States would be hugely shortsighted.

What can we do?

According to Chris Richardson, our strict immigration system acts as a scare tactic. If the U.S. can disincentivize immigration to the States in any way, it will. By creating such a long, dangerous, and potentially fruitless process, fewer people will attempt to make the United States their new home. U.S. immigration policy is a series of deterrents to potential migrants. Through his work at the State Department and as an immigration lawyer, Richardson has seen visa wait times that extend well past a lifetime. For example, for some cases in India, it would take over 100 years to get a visa. Pair that with asylum obstacles, potential detention, and countless hoops to jump through and the U.S. has created quite an uninviting environment. Yet it is important to acknowledge that a difference can be made; it isn’t only about waiting for the law to change, or changing the leadership, there are many ways to make a difference. Here are a few.

Policy change

In order for there to be immediate change to the Migrant Protection Program, the Supreme Court would have to rule it unconstitutional in early 2021. If it is not deemed as such, President-Elect Joe Biden would be able to pass an executive order to end the protocol.

In terms of broader immigration policy, we can look to a new presidency to hopefully make legislative progress, either through Congress or through executive orders. Biden has promised to change a variety of current policies, including ending the “Muslim Ban,” stopping the construction of the border wall, limiting raids and keeping families together.

Biden also has pledged to end the “Public Charge Rule.” Put in place in 2019 by President Trump, the law allows immigration officers to deny individuals visas based on their hypothetical use of federal services such as food stamps, Medicare, or public housing. Thus, if an officer judges an individual to potentially be a burden to the people, they may deem that person “inadmissible.”

Biden also promises to restore “sensible enforcement,” by immigration services. This would mean that Biden would limit ICE raids in “sensitive locations” such as schools and workplaces. Hopefully, this would also include better training for the officers so as to limit violence and maltreatment. While encouraging promises, we will have to wait to see if they are acted upon.

For a full list of what to expect from the Biden-Harris Administration in terms of immigration, check out my previous article here.

Informed voting

In this same vein, it is vital that we put individuals in office who plan to make change in areas we care about. Be sure to research the policies that your representatives and competing candidates stand for, and vote for change. One key point that Richardson offered is that we need to be vigilant about who we put in charge. We need to elect leaders who are “compassionate, who are understanding, who are ethical and who you trust […] and research to do the best.” Urging individuals from non-profits or volunteer organizations such as the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA), who specialize in these issues to run for government can help shape future legislation. It is paramount that we care about the issues that confront immigrants and refugees, but equally, if not more important that we care about the individuals running these programs. Richardson argues that they will have the most sway, as it is much “easier to change those people than it is to change the law.”

International intervention and the spotlight phenomenon

This crisis has largely avoided the international stage. This could be for a variety of reasons. Primarily, Covid-19 has been at the front of the news internationally, and the election in the U.S. has taken up much of the past six months. Additionally, this issue is rarely talked about in many circles. Immigration is often a taboo subject, and besides being extremely complex, the “ugly” parts are intentionally kept out of the way. Detention centers are in inaccessible deserts, and the MPP crisis is confined to the other side of the U.S. border and off the minds of many Americans. Finally, the U.S. is a global leader, and is very powerful. States may be scared to call out the U.S. due to fear of backlash.

International actors such as the office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights can also act. The UN has already funneled aid into Mexico, but with such a vast crisis, as well a refugee emergency in greater Central America, only so much aid can be provided.

This leaves an important role in the lap of activist groups, international human rights groups, and everyday citizens. Known as the “spotlight phenomenon” in international relations, when activist groups, citizens and the media pressure either private companies or government officials to act, they are prompted to take action.

But what can I do?

It is quite easy to research what change needs to be made by politicians, activist groups with a large platform, established lawyers and high ranking officials, but it is another to figure out what we can do in our everyday lives to make a difference. Yes, massive impactful change can be made primarily through legislative routes, but small yet immediate change can be made by anyone.

Volunteering

Many organizations need as many hands as they can get. For pro-bono legal organizations such as Las Americas, translators are in high demand. If you are bilingual, consider volunteering to translate documents or help with communications. There are also spaces to volunteer in more administrative roles.

Material and cash donations

There are many groups seeking cash donations, and everything helps. The International Rescue Committee focuses on reuniting families. Las Americas has multiple programs, including one funneling aid to those forced to remain in Mexico by the MPP. Border Kindness focuses on expanding access to medical supplies to the Mexican border. Unfortunately, common donations are not accepted at federal detention centers or holding centers; however, there are certain organizations that are able to donate. Make sure you verify with your selected organization if you want to donate to a center.

If you are unable to provide cash donations, consider material donations. Many local shelters, such as the Annunciation House in El Paso, Texas, accept clothing and food donations. If you’re going through your closet, consider donating your unwanted items instead of throwing them out or selling them.

You can also start a food drive (click here for steps on how to organize one), or a fundraiser, encouraging friends and family to help.

Finally, you can spread the word. Talk to your friends, family, and peers. Organizations such as Families Belong Together make easily shareable social media graphics. The more we collectively bring these issues into the limelight, the more change we can make.

Commit to educating yourself

That brings us to the most cliché yet most effective solution: education. When asked what he recommended to healing the immigration system, Richardson’s advice was to educate. For young people, he explains, it is vital to have knowledge about the issue, and that alone gives you “a leg up on most congressmen.” Immigration is enormously broad; if we can understand the system or at least one part of the system, we are well on our way to making change. In order to make a change, we must first be aware of the issue at hand. The more people that get behind the issue, and bring it to public attention, the greater chance a solution can be achieved.

To learn more, check out these resources:

Film

America First: The Legacy of an Immigration Raid (2018): This documentary details the impact of the 2008 Postville raids.

Well-Founded Fear (2000): This documentary depicts the interviews between immigration officers and asylum seekers.

Living Undocumented: This Netflix series follows the lives of eight undocumented families. Check out Victoria’s article about it here.

Lost in Detention: This documentary shows an investigation into Obama-era immigration policy and detention protocols.

Books

The Accidental American: Immigration and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization: This book offers a new reform of immigration, suggesting “a free international flow of labor to match globalization’s free flow of capital,” claiming that individuals should not have to risk detention or persecution for a better life.

Separated: This book comes out in 2021, and exposes the child separation policies the U.S. has in place.

Heading image: 2020, Alejandro Cegarra/Bloomberg/Getty Images/HRW

For more detailed information on immigration policy, please review the links embedded within the article.

- The United States Immigration System, and Where It Falls Apart - December 22, 2020

- What’s In Store for U.S. Immigration Policy? A Look at Immigration Under A Biden-Harris Administration - November 30, 2020

- 5 Things To Celebrate: Environmental Success Stories - November 11, 2020