There is a gap in media coverage of urban America versus rural America, making the narratives told about rural areas incomplete. Nineteen percent of the U.S. population lives in rural Census regions, but the specific challenges that these places face are overshadowed. The complexity of rural areas is often simplified to a display of county colors during election season. This perpetuates misrepresentative stereotypes, overlooking the individuality of communities and the intricate stories within them.

As an environmental science student, the case studies and research articles that are presented to me draw upon data from densely populated U.S. Census tracts. They show trends of environmental racism and use frameworks based on the clustering of humans in urban areas. As an environmental justice advocate, I struggle to think about when I have been properly exposed to movements and initiatives centered around Americans living outside cities or suburbs.

The environmental justice movement was sparked in rural South Carolina in 1982. The Warren County community mobilized to protest an extension of racism in the form of a forced toxic waste landfill. However, this story— and most of rural environmental justice— is nearly invisible and often remains untold.

When governmental agencies look at rural environmental justice, they are often labeled as socioeconomic disparities rather than identity-based. While financial inequality is an important factor in determining patterns of oppression, this gravely overlooks numerous marginalized identities while simplifying this problem in the U.S. This also causes policy and governmental practices that perpetuate racial or gender inequality to persist while concealed.

Problems like radioactive uranium mining waste in the Navajo Nation, oppressive presence of concentrated animal feeding operations, local waterway pollution, pressure on farmers to sell land to natural gas corporations, and failing sanitation infrastructure are not popularly covered. They are, however, devastating to communities and individuals.

Before uncovering specific stories of environmental inequality and injustice in rural communities, the structures that enforce this marginalization will first be explored.

Who is Rural America?

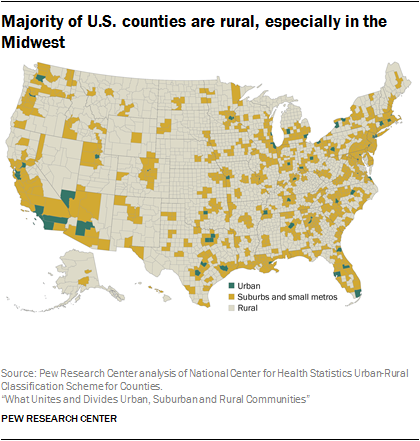

The U.S. Census Bureau defines rural as what urban is not. Urban areas are communities with a population greater than 2500 that have densely settled areas around them. The Office of Management and Budget uses a separate definition to make a distinction between metro and nonmetro, though this operates similarly. Metro areas are defined as either central counties with one or more urbanized areas of 50,000 or more people or outlying counties that are economically tied to the core counties by labor-force commuting.

Indigenous and Black people living in rural areas are more likely to report their quality of life as fair or poor than White people. Hispanic children born in rural areas are more likely to be impoverished than those in the city. Despite an overall increase in diversity of rural areas, the needs of BIPOC are not being documented or specifically addressed.

Other marginalized identities face specific challenges in rural America as well. The disability rate in rural America is higher than it is in the total U.S. population, but people with disabilities face significant economic or geographic accessibility issues. Members of the 15 to 20 percent of the LGBTQ+ community who live in rural areas also face barriers to accessing inclusive health care. Protections against discrimination in accommodations and employment are not always guaranteed.

Rural residents are more likely to be unemployed, have less post-secondary education and lower median household incomes compared to urban residents. When assessing the vulnerability of these communities to exploitation and environmental injustices, socioeconomic status and identity become compounding factors.

Persistence of Rural Undercoverage and Inequality

The framework behind the forced disadvantage of rural U.S. is similar to that of urban areas. There is a disinvestment cycle in rural areas with marginalized communities brought about by racist and discriminatory policy and practices. This occurs when the government or private sector decide that investing resources into an area will not result in a profitable return from projected community economic growth.

Many rural areas are losing more people than they are gaining. Population loss threatens economic stability and prompts government disinvestment. The link between population loss and increasing inequality is especially apparent in the rural South. This includes trends of school and grocery store closures and the scaling back of essential health care services. In Georgia, nine rural hospitals have shut down since 2008, five of them deemed critical access hospitals.

Particularly threatening in a pandemic age that necessitates virtual access, eight to 10 percent of rural America is likely to be permanently redlined by wireless broadband providers due to cost ineffectiveness. The decision to directly refuse this service is made by providers because of low population density, median household income and levels of commercial activity. A lack of internet access endangers students’ attendance at school and employees’ remote job access, perpetuating socioeconomic and educational inequality.

Generational poverty, social exclusion, and social mobility reinforce each other. To rise in class or status often necessitates living outside of your current area, especially if it is lacking in resources. Rural minorities, elderly people, and those with little education or a low socioeconomic status have few residential options that represent a step forward. These people are considered doubly disadvantaged, because they have complex needs but live in areas without resources to meet them.

In terms of financial and charitable impact, there is a rural philanthropy gap. This can be seen in Appalachian counties in Ohio that have 90 percent fewer charitable assets per capita than counties outside of Appalachia. This demonstrates a lack of philanthropic efforts to combat poverty and improve resource accessibility in comparison to organizations working to make change in urban areas.

As Emma demonstrated in her article on environmental justice, inequality is closely tied to injustice. To explore the results of this rural inequality specifically, let’s look at examples of environmental harm forced onto these communities.

Sewage and Sanitation Infrastructure

America has a dirty secret: two million Americans lack access to indoor plumbing. Because of unsafe or a complete lack of septic systems, a 2019 study found that hookworms, a parasite typically associated with extremely impoverished regions in the Global South, are recurring in rural areas of Alabama with the potential to exist in other places in the Southern U.S.

Catherine Coleman Flowers is an activist who had her first taste of advocacy growing up alongside the pinnacle of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. She began advocating for impoverished people in her hometown of Lowndes County, AL that could not afford to reinstall updated septic systems but were being fined for raw sewage. Ninety percent of Lowndes County households have failing or inadequate wastewater systems, leaving residents living alongside pools of hookworm-infested human waste.

Flowers has noted this occurrence of direct sewage piping of sewage in Kentucky, Illinois, California, and Alaska. While all of these places are rural impoverished areas, there is a direct symbolic connection in the Southern U.S. between the lack of human dignity on the land— in Lowndes, an area deep in the heart of the former Confederacy, the land has long been symbolic of the enslavement and oppression of Black people.

Inequality in Farming and Agriculture

Despite being the backbone of the functioning of our society, agricultural workers are subjected to and bear the brunt of environmental justice issues related to farming and food production. There are around three million farm workers in the U.S, most of them clustered in rural areas. Eighty-three percent of them are Hispanic.

Due to their close proximity to fields and production sites, agriculture workers are particularly susceptible to environmental toxins coming from food production. They are regularly exposed to pesticide drift, valley fever, and contaminated well water caused by chemically intensive farming practices. These toxins can also cause chronic disease and asthma through interactions with areas around agriculture epicenters where families live and children attend school.

Many rural agricultural communities lack local governance, making them vulnerable to acute environmental and climate impacts. For example, after WWII, the implementation of the Bracero Program brought Mexican agriculture workers and other communities of color to rural California. These areas still lead California to produce the highest agriculture revenue in the U.S. However, they were overlooked by municipalities as they developed, causing a legacy of unsafe groundwater wells and a lack of basic air quality protection.

About half of all farmworkers are not work-authorized, indicating that they are often migrants. Many are missed in the U.S. Census. When these residents are not accounted for, the resources provided to communities with high need are undervalued, contributing to the rural divide.

Additionally, as Izzy covered in her article on Black farmers, federal programs have forced 98 percent of black agriculture property owners off of their land. These programs are systemically racist and discriminatory, extracting billions of dollars from rural Black communities and stripping Black farmers of their often generational livelihood.

Fossil Fuel Energy Burdens

More than two million miles of natural gas pipelines run throughout the United States. West Virginia alone has seen a four-time increase in natural gas production in the past decade.

Despite being a proposed economic boost for rural areas, positive effects of fracking are not being seen: the 22 counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia responsible for 90 percent of Appalachia’s oil and gas production saw jobs, personal income and population all decline.

Powerful fossil fuel corporations use financial incentives to coerce farmers in rural America to sell land to natural gas corporations. Small and mid-sized farmers who accept deals to have companies extract natural gas via hydraulic fracturing under their land receive financial gains. The financial pull of leasing land to fracking is exploitative by fossil fuel corporations, because there is an awareness that small-scale farming is a volatile and risky business. Agreements to allow fracking are therefore “devil’s bargains.” Farmers who buy into fracking are faced with procedural inequities around negotiating and enforcing lease agreements, environmental risks accompanying unconventional natural gas operations, and outright bullying from corporations.

Farmers in the Midwest are not the only group who are vulnerable to exploitation of their land. As Elina covered in her article about fracking and native land, the Mancos-Gallup Amendment proposes 3,000 new fracking wells for oil and gas in Pueblo and Navajo indigenous regions. Allowing drilling of these lands via “leases” exploits economic vulnerability of these communities in rural southwest America. New Mexico’s last available public lands including sacred indigenous sites are threatened.

Fracking poses human health threats such as severe headaches, asthma symptoms, childhood leukemia, cardiac problems, and birth defects. Public health studies of fracking-related health effects have been complicated by medical gag rules and nondisclosure agreements between rural landowners and the fracking industry. When landowners are silenced, they cannot speak out against injustice perpetrated against them and their community. This diminishes the ability for outside forces with power and resources to bring aid to those suffering from fracking-related costs.

Seeking Environmental Justice for the Rural U.S.

The above examples of environmental injustice, like many issues of inequality in the U.S., are closely tied with discrimination against race, gender and socioeconomic status. It is important to bear in mind that where there are structural problems, there is room for impact.

Environmental injustice in communities can be hidden under other forms of injustice; applying the right lenses to address rural vulnerability can strengthen communities, improve individual livelihoods, and concurrently address environmental safety and climate resilience despite the unique challenges faced in rural areas.

Here are several recommendations for progress in policy, advocacy impact and rural community self-efficacy that can be made while addressing environmental harm:

Energy Development

Instead of viewing rural land as untapped and unutilized space to exploit for fossil fuels, we can focus U.S. renewable energy development in rural areas. Energy cooperatives are a way to support clean energy deployment in rural America by creating new jobs, establishing diverse revenue streams, and fostering innovation. Cooperatives generate or procure renewable energy within communities where they are based to anchor local economic and environmental benefits.

Another powerful example of policy is President Biden’s plans to deploy clean energy across the market. Labor support and environmental justice protection are bolstered for rural and tribal governments choosing to welcome this industry into their areas. This plan also addresses rural environmental inequalities by seeking to update infrastructure for clean drinking water and electricity grids. Grants are written into the plan to remedy legacy pollution.

Mainstreaming Rural Movements

The sanitation accessibility movement that Flowers began in Lowndes, AL demonstrates that a number of measures needed to be taken in the fight for rural environmental equality. The problem first needs to be mainstreamed: Flowers had to file numerous formal complaints, bring in numerous politicians, and even publish a book before the issue was publicized.

This can be done also by diversifying environmental advocacy groups and their leadership to include people of color, ranges of socioeconomic statuses, and residents of rural communities to bring power, force and sustainability to environmental justice movements. Tapping into the potential for women to lead activism in environmental spaces can also strengthen movements— as I noted in my article on female farmers, women often have stronger ties to land and to sustainable natural resource usage than men.

Bridging the Rural Philanthropy Gap

Charity and philanthropy will not replace government priority and support, but reducing philanthropy gaps is a step in also reducing divides between rural and urban areas. Offering more flexible grantmaking, creating support networks for rural foundations, and arranging for opportunities to further explore rural needs can build a framework to enhance financial support.

Nonprofits that target rural areas specifically can be supported financially or through volunteerism. For example, Rural Action is an organization serving Appalachian Ohio that prioritizes sectors identified by community members as being crucial to increasing stability of the area.

Towards Social Change

Keeping in mind the often slow and inefficient bureaucracy that is government-supported impact making, it is important to develop creative ways to work around a state-centric model of social change. This might look like achieving food sovereignty for rural communities and farmers by community-led local food movements. A sense of land stewardship could be developed for rural residents through encouragement to work with nature as an ally to promote environmental sustainability. Communities will be emboldened to unite against environmental injustice.

Agency should be placed back in the hands of rural communities to access, manage, and benefit from their natural resources while participating in decision-making about them. It is crucial to ensuring longevity in the ties between the rural U.S. and the Earth. Community empowerment can protect against exploitative and unjust measures taken by structural forces to disproportionately burden rural areas with environmental injustice.

Thank you for this insightful summary. I am working to bridge the rural EJ conversation, as well. Can we connect?

I am glad to hear that you enjoyed it. My email is maclaughlin_delia@wheatoncollege.edu — please feel free to contact me any time.