Housing is important. Not only as a roof over one’s head and a place to sleep at night, but also as a key factor in determining health outcomes, educational attainment, economic mobility and intergenerational wealth– or poverty.

Access to affordable, stable housing in the United States often determines whether you can currently take care of yourself and your family and whether you can improve your situation in the future, yet only 37 affordable and available homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. This represented a shortage of nearly 7 million homes before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the economic fallout from the global health crisis has only exacerbated our country’s long-standing affordable housing crisis.

Housing Cost Burdens

In any discussion of housing affordability in the U.S., the term “housing cost burden” is almost certain to appear. In 2019, 37.1 million households were housing cost-burdened, meaning they spent 30 percent or more of their income on housing, and 17.6 million were severely housing cost-burdened, spending 50 percent or more of their income on housing.

Housing cost burdens are consistently most prevalent for lower-income households in the U.S. While about 30 percent of all U.S. households (both renters and homeowners) are housing cost-burdened, that number jumps to 81 percent of renters and 64 percent of homeowners earning less than $30,000 per year. In terms of severe housing cost burdens for all households and those earning less than $30,000, the percentages similarly spike from about 14 percent to 57 percent for renters and 36 percent for homeowners.

While these 30 and 50 percent thresholds may seem arbitrary, it is important to think about how this allocation of spending impacts American families. Consider someone who works full-time for the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour and makes about $15,000 over the course of a year. 71 percent of households earning less than $15,000 are severely housing cost-burdened and are left with about $225 per month to spend on all non-housing expenses.

That means a single mother working full-time has $225 to spend on food, clothes, phone bills, transportation, medicine and anything else she or her children might need in a month. If someone gets sick or her car breaks down and the bill pushes past this spending threshold, she now has to choose between paying her rent and paying her bills.

This is what the affordable housing crisis looks like for our country’s most vulnerable households. They live paycheck-to-paycheck, stuck between providing for their most fundamental needs and experiencing homelessness.

And while the economic instability of the pandemic has certainly worsened the situation, the struggle to afford housing in the United States has been around for decades.

Before the Pandemic

One of the most important factors influencing the affordability of housing in the U.S. is the stagnation of median household incomes.

While median household incomes had been improving alongside a booming pre-pandemic economy, rental housing costs still managed to outpace median household incomes by about 12 percent over the last two decades when adjusted for inflation.

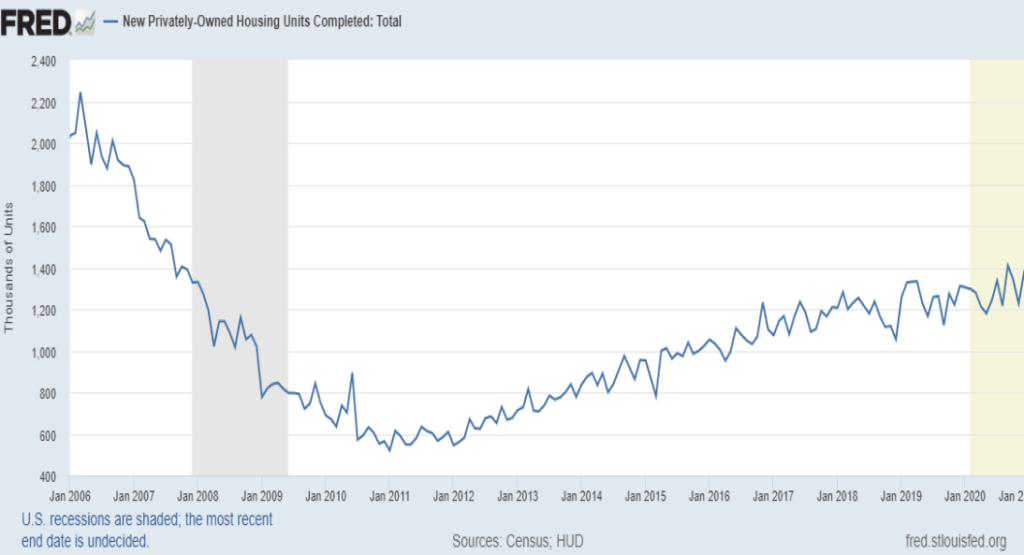

This report published in the Washington Post at the outset of 2020 detailed how exactly low- and middle-income households had been left behind by soaring housing prices. In a properly functioning market, we would expect builders and developers in the housing market to meet the demand for housing at all income levels. For newly constructed lower-income housing, that theoretically means building less expensive units that can still make a profit for developers when they are sold/rented at a lower price point.

However, there is currently a need for 1.6 million new housing units to satisfy demand in the U.S., and that number increases by about 300,000 each year as 1.4 million houses are built to replace 1.7 million lost to natural disasters, old age, etc. That 300,000 unit gap consists entirely of low- and middle-income housing because construction costs have continued to rise and household incomes have not kept pace.

The causes of higher construction costs differ in each housing market across the country, but a few common factors include zoning restrictions, fees imposed by local governments, labor shortages and higher material prices:

- Zoning regulations that are too restrictive can prevent cities from adding higher-density buildings and increasing housing supply.

- Building permit fees were raised to offset lost tax revenue from the housing crash and recession, but now they can raise the price tag of a project above what is profitable for an affordable housing development.

- Restrictive immigration policies under the Trump administration have led to labor shortages and higher labor costs in the construction, transportation, distribution and manufacturing industries.

- Tariffs and trade wars have driven up costs of imported steel, aluminum and other building materials.

As a result, builders have focused their efforts on constructing higher-end units that continue to turn a profit, and it’s not hard to see this trend playing out in cities across the country. We have a glut of luxury apartments, condos and houses on the market, but affordable housing is becoming increasingly scarce. As in any market, this scarcity is driving up prices, especially for the lowest-priced homes in any given area.

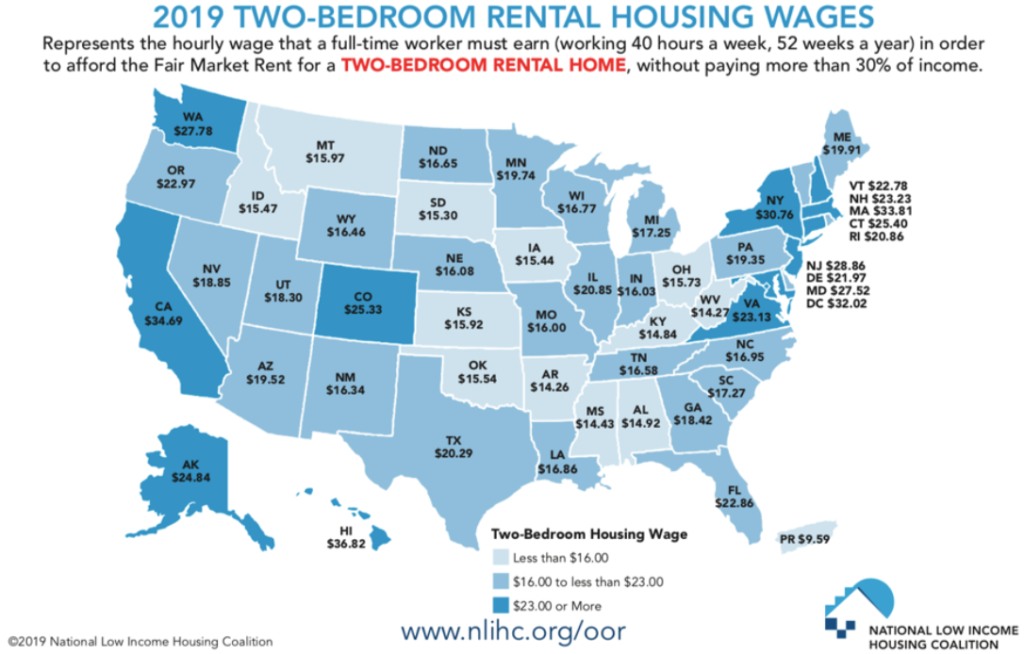

With all these factors in mind (rising construction costs, stagnating household incomes, reduced affordable housing supply), it comes as slightly less of a surprise that the National Low Income Housing Commission found that no state in the U.S. had an adequate supply of affordable and available homes for extremely low-income renters going into the pandemic.

“In 2019, a minimum wage worker could not afford a modest two-bedroom apartment in any U.S. state. In fact, it was possible to afford a one-bedroom apartment in only 28 U.S. counties while working 40 hours per week at minimum wage.”

Pandemic Effects

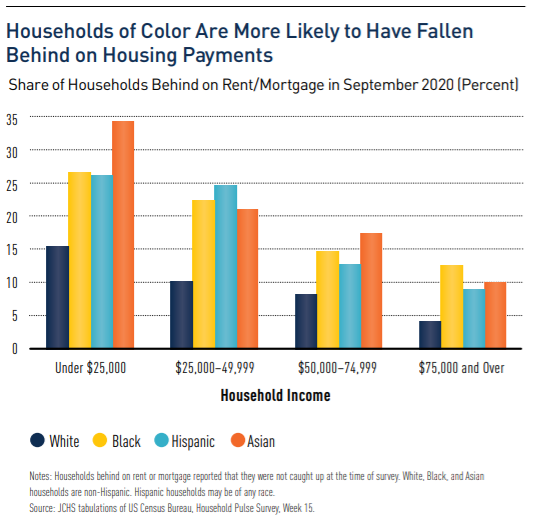

While the full effect of the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet fully known, there have been a few easily identifiable trends. Predictably, the brunt of the downturn has been borne by the most vulnerable. By December 2020, 70 percent of renters with incomes less than $25,000 lived in a household that had lost employment income during the pandemic. Households of color have been disproportionately affected as well, as shares of Black and Hispanic households behind on their housing payments are more than twice as high as that of white households.

In total, an estimated 11.4 million households were at least three months behind on their rent by the start of 2021. In a country whose renters were already facing such significant housing cost burdens, this pushed many households to the financial brink and has sparked a nationwide evictions crisis. Although stimulus checks, better unemployment and evictions moratoria have helped keep some renters afloat, these overlapping housing crises have exposed just how untenable the housing situation is for so many Americans.

Tried-and-Tested Solutions

So if an inadequate supply of affordable housing has been an issue for a while now, how have we tried to address it? Answers to this question fall into three main categories: federal housing assistance, tax incentives and funds that finance affordable housing developments.

Federal Housing Assistance

This category consists of three main programs: Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-based Rental Assistance and Public Housing. However, the largest of these and the most practical solution to focus on in the present context is the Housing Choice Voucher program. These vouchers are designed to allow low-income households to find the rental housing that best fits their needs within the private market. Assuming this housing meets the requirements of the program, this household will now only have to pay 30 percent of its income in rent – a hugely important factor in times of economic uncertainty like a global pandemic when incomes could be drastically reduced all of a sudden.

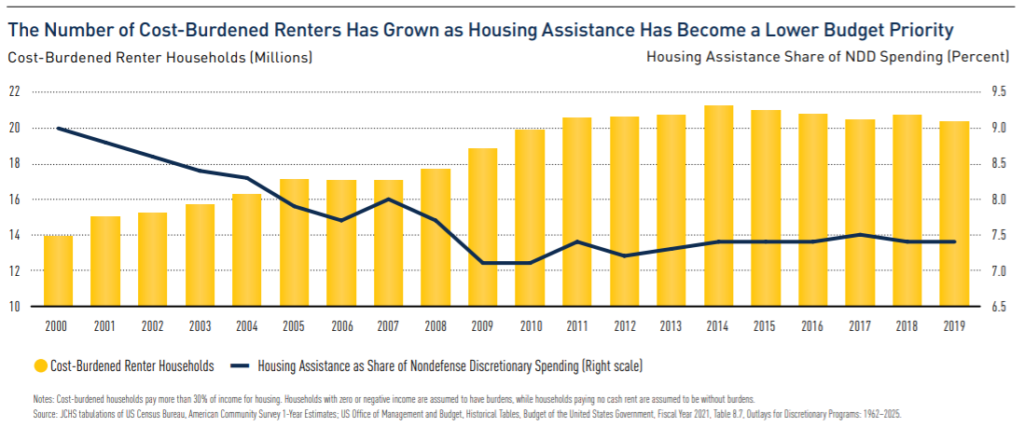

In theory, Housing Choice Vouchers and other federal housing assistance programs sound like good solutions, yet they are fundamentally flawed in their current states. Public housing projects have consistently proven harmful to tenants and residents of the surrounding areas alike, and vouchers often limit a household’s options as to where they can live and whether they can find a landlord to approve them as tenants due to widespread discrimination against tenants using vouchers. The biggest problem with federal housing assistance, however, is the lack of funding, with only one in four low-income households eligible for and in need of housing assistance receiving it. When three out of four households in need of these programs are getting nothing at all, it is clear that underfunding of these programs is severely limiting their potential impact.

Tax Incentives

Simply put, tax incentives are designed to reduce costs for developers to encourage investment in particular types of housing or locations. In the U.S. today, there are three main tax incentives that are meant to encourage affordable housing investment. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is the oldest and most important of these, having supported the construction of about 110,000 units per year since the mid-1990s with a cost of about $8 billion per year in forgone tax revenue. LIHTC is unique among these tax credits in that it can only be used to develop or rehabilitate affordable housing units. The New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) and Opportunity Zones (OZ), on the other hand, are meant to stimulate investment of any kind within lower-income areas that typically struggle to attract investment.

Of the three, LIHTC projects are by far the most effective at creating affordable housing supply. Not only are they specifically intended to do so, but they are also allotted to states to distribute as they see fit. This allows LIHTC projects to be paired with other state and local tax incentives to maximize their value. Additionally, the NMTC and OZ incentives have been found to be less effective at increasing net investment (instead, just shifting it from one area to another), provide limited benefits to local employment and can cause displacement resulting from gentrification. Thus, the LIHTC program has historically been the most effective tax incentive solution for increasing the supply of affordable housing and could easily be bolstered going forward.

Housing Trust Fund & Capital Magnet Fund

These two federally managed funds were created to allocate funding for increasing the supply of affordable housing through new construction, reconstruction, acquisition, or rehabilitation of non-luxury units. The Housing Trust Fund provides block grants to state housing authorities for the development or preservation of housing targeted to extremely low-income households (those with incomes at or below 30 percent of the area median income or below the federal poverty line) that must remain affordable for a minimum of 30 years. The Capital Magnet Fund, on the other hand, awards funding to non-profit organizations that can be used to finance affordable housing activities and “related economic development activities,” to attract private capital.

The benefit of the “federal funds” strategy is that it gets resources into the hands of those in a better position to understand and address each area’s particular affordable housing challenges. The federal government has the money, but state housing authorities and housing non-profits know how best to spend it. Now that both funds have been operating for over a decade, this solution is particularly valuable because the infrastructure is in place to scale up quickly. Recently, the federal government demonstrated this ability to scale up by allocating a record $1.09 billion in funding between the two funds, more than doubling the previous year’s total.

Up-and-Coming Solutions

In addition to these tried and tested solutions, new approaches to tackling the affordable housing crisis are emerging all over the U.S. Two of the major reasons that low- and middle-income housing is no longer economical for developers relate to zoning regulations and the cost of labor and materials.

Zoning

While zoning may seem like a boring, bureaucratic necessity, the reality is that it has profound effects on how our cities operate. Thus, cities around the country are beginning to re-examine restrictive and outdated zoning codes that prevent the creation of affordable housing, often driving up housing costs and reinforcing geographical patterns of racial and economic disparities. Most famously, Minneapolis has eliminated zoning for single-family housing, allowing buildings of up to three units on any of these lots. Even less radical steps like easing height and density restrictions in certain areas have proven effective, allowing developers to meet the market’s demand for housing.

Prefabricated/Modular Construction

To address the problem of rising costs throughout the construction industry, some developers have turned to prefabricated, modular construction techniques that could revolutionize how our cities are built. Traditional construction techniques in urban areas are expensive, noisy, disrupt traffic and can take years to complete.

Prefab, on the other hand, can create all the necessary parts for the building in an off-site factory, potentially solving all of these problems while using less energy in the process. Centralizing construction activities in the factory reduces the amount of labor needed in cities where it is most expensive and difficult to find, standardizes the components to produce them faster and more precisely and these components can be assembled on-site in a matter of days or weeks.

Imagine that, an entire building put together like Legos in the middle of a dense urban environment with a fraction of the noise, disruption and time. That’s the dream of prefab, modular housing, but there are still plenty of hurdles to clear before it becomes a reality.

What Can Be Done?

Let’s return to that initial statistic: there are 37 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. We know what this means for low- and extremely low-income households: housing cost burdens and choosing each month between paying rent and affording necessities like food and transportation. We know how stagnating incomes and an insufficient supply of affordable housing created a crisis in which no state in the U.S. had an adequate supply of affordable and available homes for extremely low-income renters before the pandemic – which, of course, has only exacerbated these problems by disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable households.

Addressing a nationwide affordable housing crisis requires all of the solutions mentioned above along with further legislation and innovation. Housing choice vouchers need sufficient funding for all eligible households to receive assistance. Programs like LIHTC and the federal housing funds should be expanded and refined to create and maintain affordable housing. Developers and local governments should seek to innovate with prefab building methods and zoning reforms to increase housing stock in a way that meets economic and equitable urban planning requirements.

More than anything, however, legislation is needed to increase the minimum wage and strengthen the social safety net. Low-income households need to be able to afford housing without taking on oppressive cost burdens, and the market will eventually meet the demand for affordable housing when these households can afford rent that covers increasing building costs.

In the short term, both “tried-and-tested” and “up-and-coming” solutions are critically important to improving the affordability of housing for low-income households. In the long-term, however, legislation is needed that addresses broader, systemic issues in the U.S. economy and aims to reduce growing wealth and income disparities. When household incomes begin to keep pace with construction costs again, the market will supply affordable housing better than federally funded programs ever could.